———————————————————————————————————————————————————

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Joint Hearings

before the

Committee on Education and Labor, United States Senate

and the

Committee on Labor, House of Representatives

Seventy-Fifth Congress

First Session

on

S. 2475 and H.R. 7200

Bills to provide for the establishment of Fair Labor Standards in Employments in and affecting interstate commerce and for other purposes

June 2 to June 5, 1937

Printed for the use of the Committee on

Education and Labor

United States Senate, and the

Committee on Labor, House of Representatives

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASINGTON: 1937

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE ii]

COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR

UNITED STATES SENATE

HUGO L. BLACK, Alabama, Chairman

ROYAL S. COPELAND, New York

DAVID I. WALSH, Massachusetts

ELBERT D. THOMAS, Utah

JAMES E. MURRAY, Montana

VIC DONAHEY, Ohio

RUSH D. HOLT, West Virginia

CLAUDE PEPPER, Florida

ALLEN I. ELLENDER, Louisiana

JOSH LEE, Oklahoma

WILLIAM E. BORAH, Idaho

ROBERT M. LA FOLLETTE, JR., Wisconsin

JAMES J. DAVIS, Pennsylvania

KENNETH E. HAIGLER, Clerk

COMMITTEE ON LABOR

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

WILLIAM P. CONNERY, JR., Chairman, Massachusetts

MARY T. NORTON, New Jersey

ROBERT RAMSPECK, Georgia

GLENN GRISWOLD, Indiana

KENT E. KELLER, Illinois

MATTHEW A. DUNN, Pennsylvania

REUBEN T. WOOD, Missouri

JENNINGS RANDOLPH, West Virginia

JOHN LESINSKI, Michigan

JAMES H. GILDEA, Pennsylvania

EDWARD W. CURLEY, New York

ALBERT THOMAS, Texas

JOSEPH A. DIXON, Ohio

WILLIAM J. FITZGERALD, Connecticut

WILLIAM F. ALLEN, Delaware

GEORGE S. SCHNEIDER, Wisconsin

SANTIAGO IGLESIAS, Puerto Rico

RICHARD J. WELCH, California

FRED A. HARTLEY, JR., New Jersey

W. P. LAMBERTSON, Kansas

CLYDE H. SMITIH, Maine

ARTHUR B. JENKS, New Hampshire

MARY B. CRONIN, Cler.:

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE iii]

CONTENTS

Statement of

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 997]

United States Senate,

Joint Committee of the Senate Committee on

Education and Labor, and House Committee on Labor,

Washington, D. C.

The joint committee met, pursuant to adjournment, at 10 a. m., in room 857, Senate Office Building, Senator Hugo L. Black presiding.

Present: Senators Hugo L. Black (chairman), Allen J. Ellender, Robert M. La Follette, Jr., and James J. Davis; and Representatives Robert Ramspeck, Glenn Griswold, Matthew A. Dunn, Reuben T. Wood, James H. Gildea, George J. Schneider, William P. Lambertson, Arthur B. Jenks, Clyde H. Smith, William J. Fitzgerald, and Albert Thomas.

The Chairman. Mr. John B. Scott. Before we proceed with Mr. Scott I will state for the record that the committee agreed, at the last meeting that we had concerning the hearings, that we would have witnesses last Thursday up to last Friday and that then we would close the hearings. We had witnesses summoned for Thursday and Friday, but on account of suffering the tragic loss of our colleague, Mr. Connery, those hearings were postponed until today and tomorrow. So, under the agreement that the committee had, the hearings will be closed tomorrow. That will permit to come before the committee every witness who has requested to testify up to this time. We have today 10 witnesses. Tomorrow we have seven witnesses on the list, but there are several others who have asked to be heard, and, in order to carry out the understanding of the committee, I have asked them also to come tomorrow.

I am making this statement at this time so we will understand that we are carrying out the agreement made by the committee, except that we have substituted today and tomorrow for Thursday and Friday of last week.

Representative Thomas. Mr. Chairman, before you proceed, I would like to make a statement. Our colleague, Congressman Dixon, of Cincinnati, is ill. Mr. John H. Clippinger, the president of the Gerrard Co., of Cincinnati, is scheduled to appear this morning. The Congressman wishes me to state to Mr. Clippinger that he is very, very sorry that he cannot be here this morning on account of illness. I think the committee is sorry to hear of that.

The Chairman. Yes; we very much regret hearing of Mr. Dixon’s illness.

This is Mr. John B. Scott of the Anthracite Institute.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 998]

The Chairman. Mr. Scott, you were requested to appear before the committee. We will be glad to hear you.

Mr. Scott. Mr. Chairman and gentlemen, the Anthracite Institute, a trade association, representing substantially all of the anthracite producers in the United States, desires to record its opposition to the favorable consideration by your honorable committees of S. 2475 and H. R. 7200, and the proposed Fair Labor Standards Act of 1937.

We are advised that the measure as it is now written is subject to serious constitutional objections. It seeks to control labor conditions in business purely local and intrastate in character, where the goods thus produced come into competition with goods shipped across State lines. Such an application of the commerce clause of the Constitution, used as a basis for this legislation, would in effect obliterate State lines and local self-government and thus destroy the fundamental separation of powers between the Federal Government and the States, which separation is the very basis of the Federal union.

Moreover, the measure in many of its aspects presents an unparalleled picture of delegation of undefined legislative power by the Congress to an administrative board. Such delegation has many times been condemned by the Supreme Court of the United States.

It has been established by recent decisions of that Court that the States have reasonable control of minimum wages. Per contra, it is equally clear that in no recent decision of the Supreme Court is support given to the doctrine that, under the guise of regulating commerce, Congress may control hours and wages.

The proposed Fair Labor Standards Act represents an application of unsound economic principles. The measure will afford foreign competitors an opportunity for trade invasion. It will cause rising costs and therefore curtail the purchasing power of the great majority of the American people. The proposed bill seeks to establish a maximum above which hours of work may not rise and a minimum below which wages may not fall, notwithstanding that in certain industries, at certain times and under exigencies of the most compelling nature some reasonable, although perhaps temporary, adjustment may be necessary for the public good.

The proposed act is unsound from the point, of view of the public policy of the United States, particularly the policy dealing with industrial relations. By its terms it is intended to supplement the National Labor Relations Act, but in so doing it would in effect divide the administration of that act and seriously modify the beneficial effects sought to he derived from that statute. No justification can be found for conflicting administration of measures in the vital field of labor relations.

In this connection we desire to propose that, if your honorable committees are disposed to act favorably upon this measure, the act. as finally drawn up should provide reasonable social standards and controls of labor combinations operating in the field of commerce. The public must be protected against the constant interruption of commerce without just cause, whatever the source of such interruption. Tyranny and coercion, whatever their origin, should be condemned.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 999]

We urge your honorable committees to disapprove these bills.

The Chairman. Thank you, Mr. Scott.

If there is no objection on the part of the committee, I am going to substitute for the next witness, who is Mr. Alldredge, of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the third witness, Mr. Horace Herr, and after that we will call Mr. Alldredge. We will hear Mr. Horace Herr, of the National League of Wholesale Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Distributors.

Mr. Herr. Mr. Chairman and members of the committee: This statement has been authorized by the advisory board of the National League of Wholesale Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Distributors, a nonprofit, incorporated trade association with a membership of more than 500 wholesale distributors of fresh fruits and fresh vegetables. The membership is drawn principally from east of the Mississippi River. Included in it are growers, shippers, brokers, commission merchants, and f. o. b. buyers, and jobbers.

Since H. R. 7200 and S. 2475 were introduced in the Congress on May 24, there has not been time to take a referendum which would disclose the sentiments of the membership toward this specific legislative proposal. However, under the constitution and bylaws of the organization, it is the responsibility of the advisory board to “handle all matters of emergency and the general affairs of the National League not otherwise provided for, at all times except when the National League is in annual or special meeting.” It is obvious, therefore, that while this statement has the approval of the advisory board, the views expressed may not be shared by all members of the organization.

Wages and the hours for employment have been under discussion for many years and were before this industry for action in connection with a code established under the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 and 1934. Several legislative proposals before the Congress during the last 4 years have promoted widespread discussion in all industries. The basic issue involved was prominent in the last national election. The attitudes within this industry, therefore. are known to the advisory board, even though it does not have an expression from its membership on the specific program now under consideration. On the basis of this general knowledge, these representations are made.

The principles of a minimum legal wage and maximum hours for the legal workweek are accepted as desirable.

The approach to the problem, through regulation of interstate commerce, is accepted as logical, although there is room for doubt on that score of practicability.

The necessity for elasticity in the application of minimum wages and maximum hours, to conditions which show marked variation among the several industries is obvious to those who deal with the realities of a complicated industrial system. The real problem is to preserve as much uniformity as is possible without impairing the ability of the industry to employ workers and to produce goods at a price that will promote their maximum movement into consumption.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1000]

The preservation of maximum uniformity, in the application of this program, or, to state it another way, the preservation of minimum variation from the program, involves such a multitude of details that the Congress could not possibly write into a law provisions which would anticipate and deal with each and every situation. The establishment of an agency, such as the proposed labor standards board, therefore, is accepted as a practicable method for meeting this situation.

In no spirit of hostility to the basic features of this bill, but with a desire to be helpful to those who must make the final decisions on these questions, and with a sense of obligation to do what can be done to protect the members of this association from business hazards which, without intent to do so, the Congress might impose on them by this type of legislation, some of the formidable difficulties in applying this program to the fresh fruit and vegetable distributive industry are here presented.

This organization is not “urging” the passage of this bill. The possibilities of attaining the desirable objectives, without confusion that would more than offset the anticipated benefits, are by no means certain. If it is the considered judgment of the Congress, responsible to the people for the preservation of orderly Government under the Federal Constitution, that the time has come when the general welfare requires an experiment in this field, we shall make a forthright effort to cooperate, asking only a continuing respect for the traditional principle of maximum liberty of action consistent with national security.

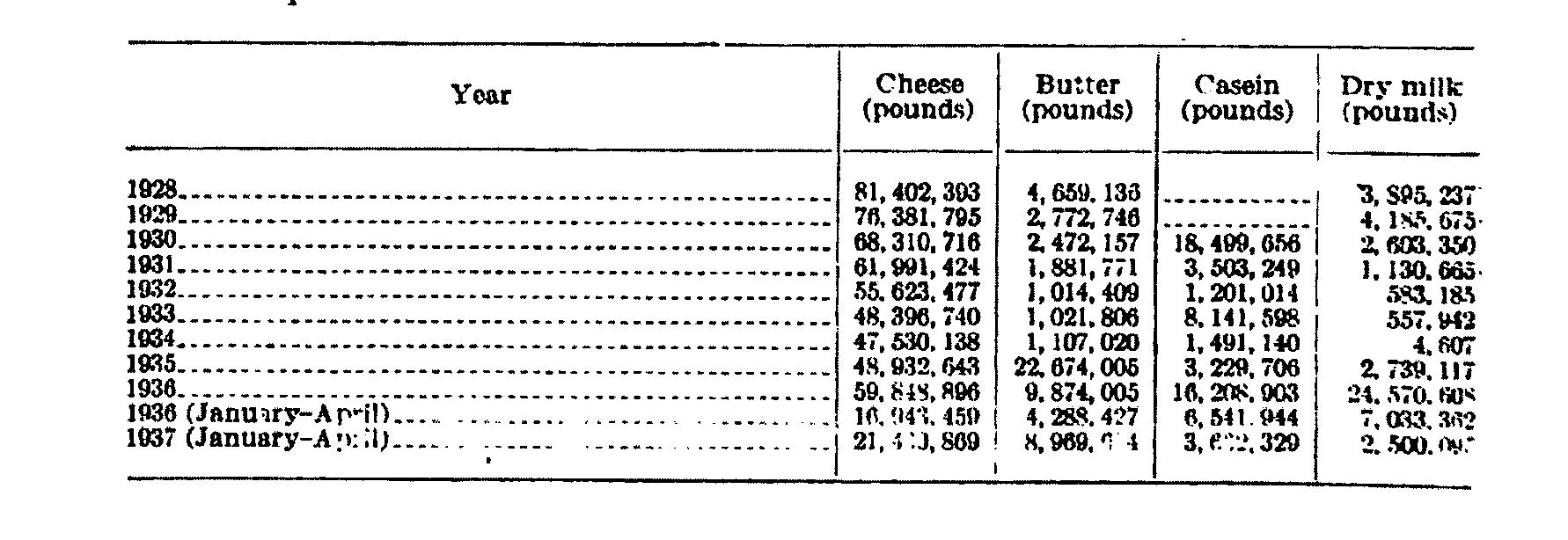

In 1934, in connection with code negotiations under the National Industrial Recovery Act, a survey indicated that approximately 60 percent of the annual carlot movement of fresh fruits and fresh vegetables was handled, in some capacity, by the members of this association. The average annual movement of these commodities for the 8 years 1928-35, inclusive, was 857,794 carloads by rail and boat. Only fragmentary data on movement by motor truck are available. These suggest that about one-third of the total volume of commercial fruits and vegetables move to market by motor truck. This makes an annual movement of at least 1,000,000 carloads a year.

Figures in the United States census of 1930 and the census of American business for 1933 and 1935, as published by the United States Department of Commerce, present the following statistical picture of the wholesale fresh fruit and vegetable distributive industry:

Number of establishments: 1929, 11,194; 1933, 9,083; 1935, 9,642.

Net sales at wholesale: 1929, $3,252,975,000; 1933, $1,733,284,000; 1935 $2 008 503 000

Total expenses: 1929, $260,538,461; 1933, $174,646,000; 1985, $181,- 884,000.

Number of employees: 1929, 92.799; 1933, 68,103; 1935,74,810.

Salaries and wages: 1929, $123,627,601; 1933, $79,032,000; 1935, $87,146,000.

Due to differences in classifications, the figures for 1929 are not entirely comparable with those for 1933 and 1985. They are indicative rather than conclusive. Obviously they do not include all establishments handling fresh fruits and fresh vegetables in interstate commerce. Under the Perishable Agricultural Commodities

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1001]

Act, enacted at the request of this industry in 1930, those engaged in wholesale distribution of these commodities, in interstate commerce, are required to take out a license from the United States Department of Agriculture. As of June 30, 1933, there were 14,347 licensees, 15,697 in 1935 and on June 1, 1937, there were 17,932 licensees under this act. This suggests that the Department of Commerce figures are not inclusive enough to give a complete picture. They are inclusive enough to give a reliable index. On the basis of the present number of licensees under the Perishable Agricultural Commodities Act, it is safe to say that more than 100.000 persons are employed in this industry with total annual wages of approximately $150,000,000,

When it comes to rates of returns on the distributor’s investment, there is no inclusive data and very little that is acceptably authoritative. The Federal Trade Commission, in a statement released June 10, 1937, summarizing findings based on recent investigation of the fresh fruit and vegetable industry, stated:

Rates of return for wholesale distributors were lower than the other two groups (chain-store distributors and canners and packers) during the 7-year period (1028-35), during which the returns for 94 wholesale distributing companies averaged 4.64 percent. Returns were highest in 1929 with 9.12 percent, and lowest in 1932 with a loss of 1.7 percent. In 1983 the returns recovered to 4.05 percent, followed by an increase to 7.65 percent in 1934, but in 1985 they declined to 4.98 percent (These figures are returns on “investment.”)

A survey made within this organization for 1932 showed that 25 firms with total net sales of $16,550,998.55 had a deficit of 1.3 percent of the total net sales. In other words, the gross margin between the cost of goods and the sale price was $1,170,750.12 and operating expenses were $1,386,441.35. The labor item in total expenses was $919,898.54 or approximately 78 percent of the gross margin between cost of goods and net sales revenue.

The research and statistical division of Dun and Bradstreet in 1935 issued the results of an analysis of the 1933 operating averages of 39 wholesale fruit and vegetable concerns with total net sales of $25,150,609. Of these, 24 firms, with net sales of $18,264,972, showed a gross profit of 15.30 percent and a net profit of 1.85 percent. On the other hand, 15 firms, having total net sales of $6,885,637, showed a gross profit of 15.16 percent and a net loss of 1.67 percent.

In the highly competitive terminal markets east of the Mississippi River, commission merchants handle at least 50 percent of the volume of these commodities, as agents for the growers or shippers. The commission rate is more often below 10 percent than it is above. On consigned business the commission fate is the gross margin out of which must be paid expenses, return on investment, and profit, if any.

These facts suggest that this is a narrow-margin industry and those operating in it are, quite naturally, alarmed when any proposal is made to increase their operating costs. The question of how to meet the increase cannot be taken lightly. Perishable commodities do not lend themselves to arbitrary prices. There was no price-fixing in the N. R. A. code for this industry. N. R. A. was willing but the industry would not have it, knowing it would not work. The consumer and his buying power are the determining price factor, peculiarly so because always he has a choice of substitutes for the commodity which he believes to be selling at too high a price.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1002]

Logically, this industry might expect to benefit through increase in both volume and price, to some unpredictable degree, if the fixing of a minimum wage and reduction of hours throughout all industries increased purchasing power. It is difficult, however, to be reconciled to a certain and substantial increase in expense by contemplating an uncertain increase in volume and price.

As it takes on major importance in this industry, the first reference is made to section 6 (a), page 17 of S. 2475, lines 3 to 12, inclusive. The exemption of employers on the basis of the number of employees they might have would set up intolerable competitive conditions in this industry. The suggestion made by the Secretary of Labor in her testimony before this committee, that this provision for exemption on the basis of the number of employees be eliminated, is concurred in. If a minimum wage and the maximum hours for the workweek are to be set for this industry, they should apply to all employers regardless of the number oi employees. This is a highly competitive industry and contrary to popular notions, it is an industry operating on very narrow margins. In every market, the price level reacts almost immediately to a low price sale, even though it may be under the general level by but a cent or two. The consequences of the competitive situation resulting from exemptions as now provided in this provision, inevitably would tend to decrease the returns to the grower. In this industry, as a rule, the low wages and the longest workweek are found in the operations of the small establishments. The experience of this industry justifies the conclusion that this type of exemption is not a sound policy, and, if applied, would promote decidedly unfair competition. As far as this industry is concerned, once a minimum wage has been fixed with due considerations for the characteristics of the industry, payment of the wage should be the obligation of every employer.

In section 2 (a), in connection with the definition of “employee”, in paragraph 7, lines 3 to 11, page 4, the question is raised as to whether the Board should decide where the line should be drawn between agricultural labor and labor within the scope of the act, or Congress should draw the line? Is it the congressional intent that this program shall be as inclusive as possible, or that its application should be restricted so as to impose none of its obligations upon employers engaged in activities directly affecting agriculture or inseparably intertwined with agriculture in the marketing processes? It may be that wherever the line is drawn, some injustices may result both to the employees, on the exemption side of the line, and to the employers, on the inclusion side of the line, the injustices to the latter resulting from the labor-cost differential. This question is of some importance in this industry, where the commodities move in their natural state, where certain handling operations are dictated by the highly perishable character of the commodities, and where actual ownership, to a substantial extent, remains with the producer until the commodities are bought by the retail outlet; when the cost of grading, packing, loading for shipment, storage, and other marketing expense is charged back to the grower. There is involved in this question, the cooperative packing plants and marketing associations and the movement of commodities, such as apples, into and out of storage. In the Social Security Act, agricultural labor is exempt and the definition of agricultural labor rests with the Commissioner of

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1003]

Internal Revenue. There has been considerable pressure to liberalize the definition. In the fruit and vegetable code, as approved by both N. R. A. and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the line was drawn at the point where the commodity was on board the transportation facility, the code language being as follows:

The Industry as defined shall not include the production nor preparation, assembling, or loading at point of production of commodities for shipment.

It would seem that fixing the limit on agricultural activities in a program of this kind, so directly relates to the national policy for agriculture, that the Congress, rather than the Labor Standards Board, should draft the formula for the dividing line. The Congress, at least, should say whether the doubt is to be resolved in favor of the workers or in favor of the farmers.

Paragraph 10 of section 2 defines the term “oppressive wage”, and it is proposed to state, in the definition, the amount per hour which shall be the minimum wage, the Labor Standards Board having authority to vary from the stated minimum under certain conditions. The minimum wage imposed on this industry by the N. R. A. code ranged from 25 cents an hour in towns of less than 25,000 population in the South, to 331/3 cents an hour in cities with 500,000 or more population in the North. A survey by N. R. A., covering the workweek of June 15, 1933, indicated about 20 percent of employees in this industry were paid $15 or less per week. A survey made within the membership of this organization about the same time, indicated about 6 percent of the employees were paid less than $16 per week. The figures for the membership of this organization would not be representative of the entire industry as these members are the older, experienced firms, probably able to attract the more efficient labor with wages somewhat higher than the general level. There is a limit to how high the efficient distributor can go in increasing wages and an important factor in that limitation is the competition he must meet from the low-wage distributor.

A study made in 1933 by Dr. John R. Arnold, Division of Economic Research and Planning in N. R. A., indicated that 2,172 employees out of a total of 9,922, in this industry, during the week that included June 15, had weekly earnings of less than $15. Keep in mind that June is a very active season in which this industry employs more than usual temporary or occasional labor. The figures are based on what the employee actually earned during 1 week and do not necessarily indicate the wage per hour which he may have been paid. To increase the earnings of these 2,172 employees to $16 a week on the basis of a 40-hour workweek, would mean an increase of about 28 percent on 20 percent of the total labor force involved in the study. This figures out as an increase of 2.77 percent in the total labor cost for the 9,922 employees involved in the survey. This is figured on a 40-hour-week basis, but these 9,922 workers actually were not. on a 40-hour basis. The majority of the full-time employees were working 48 hours to as many as 70 hours.

This brings us to the definition of “oppressive workweek”, section 2 (a), paragraph (11) and the other provisions of the bill dealing with the proposed standard of hours.

This is, necessarily, a long-hour industry, especially in the summer. The long hours apply to the employers as well as to the

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1004]

employees. These commodities must be harvested, shipped, sold, and consumed when they are ripe. Nature controls the ripening factor. Beginning with Florida products in the winter, the growing and marketing season moves north and west. Each growing section brings a rush movement. At one season the rush is on Florida vegetables, at another Georgia peaches or watermelons. The peak movements follow one upon the other, often overlapping. Finally comes the heavy local production in all the Northern States. The products must be marketed when they are ready. The wholesale distributor has no choice but to take care of the supplies when they arrive, and, with large truck movement, they now arrive every hour of the day and night. Long hours cannot be avoided. If the Congress decides that this industry, intimately connected with agriculture, should be included in such a program as is contemplated in this bill, then some place there must be authority to modify the program to meet the difficult and unyielding conditions which the industry faces—conditions which exist not by choice but by necessity. The industry is under constant pressure to decrease the cost of distribution. Decreasing the cost of distribution is, of course, impossible if Federal laws continue to increase those costs. This industry is willing to go along on this program to the extent that it can absorb the increase and continue solvent. Its experience is that it cannot possibly maintain its solvency on a minimum wage of 40 cents an hour if the workweek were reduced to 40 hours, or 44 hours or even 48 hours, applicable to all its employees.

Keep in mind the fact that this is a “hand labor” industry in which the possibilities for mechanization are decidedly limited.

To write into this bill a positive limitation of the Labor Standards Board’s discretion to vary hours to meet conditions as found in the several industries would be dangerous. A safer procedure would be to specify the number of hours which the Congress finds is a desirable objective, leaving it to the Board to promote adherence as closely as is consistent with the characteristics and conditions of the industry involved.

In connection with section 23 (a) and (b) (p. 40, line 21, and p. 41 to line 14), we are impelled to point out that no group has a monopoly on the abuse of power. Given the power, farmers, industrialists, workers, and even governments abuse it. We venture to suggest that the general tone of some of the provisions in this bill is not conciliatory or likely to encourage employees and employers in seeking better understanding of their respective problems. The time surely must come when organized labor must accept more responsibility for its acts than it now carries. Two suggestions are offered to this committee for consideration.

If and when the Labor Standards Board, by order establishes a minimum wage and maximum workweek and an industry is meeting the conditions as to these and other labor practices, is it unreasonable to ask that a labor organization, active in that industry, will refrain from strike for a definitely specified time during which time negotiations are in progress? In other words, why not give this Labor Standards Board authority publicly to condemn a strike when called before negotiations had been under way a specified period, say, for example, 90 days? All the conditions and penalties imposed by this bill are imposed upon employers. The bill proposes

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1005]

to take away certain rights which employers, as citizens, heretofore have had. Since all the certain benefits accrue to labor, if these benefits are as substantial as they are represented, it would seem reasonable to expect labor to make at least a gesture of concession in the interest of industrial peace.

The other suggestion is that this labor standards board might be given authority and the responsibility of publicly condemning a labor agreement negotiated by one group of employers and a labor organization, when the effect of that agreement was to victimize or penalize a third group which had little if any voice in the negotiations or agreement.

The Federal Trade Commission, in its investigation under a congressional resolution, found conditions which it discusses in its report sent to Congress by June 10. The following is quoted from a statement issued by the Commission on that date:

The report shows that monopolistic and racketeering practices in the carting of fruits and vegetables exist in several of the larger terminal markets, particularly in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. In New York and Chicago, the truckers, with the assistance of teamsters’ union, have obtained a monopoly of the commercial hauling of fruits and vegetables from the principal terminals by excluding all trucks not members of the truckers’ associations or whose drivers do not belong to the local union. Measures in this direction also have been taken recently by the truckers’ association in the union local In Philadelphia. In some of these markets, particularly in Cleveland and Chicago, agents of the union have by threats and intimidation forced outside trucks bringing produce from producing areas into the market to pay for the privilege of unloading.

This subject was discussed in detail in a previous report of the Federal Trade Commission on its investigation of the potato industry. The details cover some 56 typewritten pages of a report now available in the office of the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry. If the responsible leaders of organized labor are indifferent to or powerless to deal with racketeering groups which worm their way into union organization, then they should approve and support some provision for the public condemnation of the so-called labor agreements which take on the characteristics of rackets.

It may be, that after considering the difficulties which this program would encounter in the fresh fruit and vegetable industry, the committee will see some merit in the suggestion that a special provision is desirable for this industry, leaving the question of minimum wage and maximum hours to be determined by investigation and hearing, and placing the administrative authority for this industry with the U. S. Department of Agriculture from which the members of this industry now hold their Federal licenses.

The Chairman. Thank you very much. Mr. H. F. Waidner, Jr., of Henderson, Linthicum and Co.

Mr. Waidner. Mr. Chairman and members of the committee: Mr. Horace Herr, who is the secretary of our association, has presented a formal brief on our stand in reference to this proposed bill before Congress.

The Chairman. What association is that?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1006]

Mr. Waidner. The National League of Whole Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Distributors. I wish to appear before you as a practical commission merchant, in other words, one of these fellows who handles farm commodities on a consignment basis. My business is in Baltimore, Md. I conduct a business there where 90 percent of the fresh fruit and vegetables that we receive from points of origin are handled by us on a commission basis.

Now, theoretically, the charge for commissions in handling these commodities is 10 percent, but it very, very seldom works out that way. I believe that any of you gentlemen who are familiar with the general write-up in profits in the wholesale business will realize that even 10 percent margin is a small margin to work on, but while we are theoretically supposed to charge 10 percent commission most of the time we are obliged to charge only 7 percent commission, and our average commission rate runs between 7½ and 8 percent.

We are opposed to this bill which is proposed in Congress for the simple reason that it is going to add more cost to our business and will, therefore, be a further detriment to our being able to conduct our business with any thought of making a profit.

Representative Ramspeck. Is that 10 percent gross or net?

Mr. Waidner. Ten percent gross; yes, sir.

Representative Ramspeck. You have to take all of your operating expenses out of the 10 percent?

Mr. Waidner. Everything comes out of the 10 percent, but, as I say, that is the theoretical amount of commission that we are supposed to charge. Actually, when you give rebates to agents, when you give concessions to shippers whose produce you want to keep lined up it boils down, in a great many cases, to 7 percent commission. As I say, in 2 or 3 years’ work our average commission over the years has been 7½ to 8 percent.

Representative Dunn. How many people do you employ?

Mr. Waidner. I employ 17, which is my misfortune, because under this act, as I understand it, the employer who employs less than a certain number of people will be exempted from this thing, just the way it is under the Social Security. Am I right in that?

The Chairman. The committee has not passed on that.

Representative Dunn. How many hours a day do your employees work?

Mr. Waidner. That depends upon the season.

Representative Dunn. I mean during your busy season.

Mr. Waidner. During the busy season they work between 10 and 11 hours, very seldom over 11 hours.

Representative Dunn. Seven days a week or 6 days a week?

Mr. Waidner. Six days, but on Saturday, of course, we have what is supposed to he a half day holiday and we usually get out between 1 and 2 o’clock in the afternoon.

Senator Ellender. How much do you pay your labor?

Mr. Waidner. Beg pardon?

Senator Ellender. How much do you pay your labor?

Mr. Waidner. The store labor averages between $16 and $20 a week. The people who have the trucks, who back in and unload them, pile the produce on the sidewalk or in the warehouse where it is displayed for sale, they average between $18 and $20. The

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1007]

drivers in Baltimore, as far as Baltimore is concerned, we pay $20 to $22 a week.

Representative Ramspeck. I do not want to interfere with your statement, but I hope you will give the committee, at some point, a practical statement of how you operate, what the difficulty might be to your particular operation under this bill.

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Senator Ellender. In connection with Congressman Ramspeck’s question will you also tell us when your most busy season is and now long it lasts as a rule?

Mr. Waidner. We are always busy. In other words, the thing I would like to bring most forcefully to the attention of this committee is the fact that we are constantly riding along on the crest of somebody’s crop time. In other words, a man in Florida, along in January, is starting on his crop of tomatoes. There is nobody that can go out in the field and say that these tomatoes are only going to grow 8 hours and after 8 hours they are going to stop growing. Those tomatoes are brought on to the market to be distributed. When the tomato-shipping season out of Florida begins is when we run into the busy season, handling Florida tomatoes, and it runs right up the coast that way. Then when the fellow who has been shipping tomatoes drops out of the picture his place is immediately taken by the man who is shipping strawberries in the northern part of Florida, and then we go up the coast of Georgia and there is a constant recurrence of the period of crop time in this industry.

If there is any dull time at all in the industry it might be perhaps in the wintertime, which is, presumably, supposed to be the dull period in the business, but now, with the tremendous increase in fresh fruits and vegetable production and consumption by the American people you find the producers in California, Texas, New Mexico, and Florida amply supplying the market with fresh fruits and vegetables, which keep us constantly busy.

Senator Ellender. During the dull period do you keep all your employees on?

Mr. Waidner. I do; yes, sir.

Representative Thomas. May I interrupt you just a minute? I do not quite understand the nature of your business. Are you a wholesaler in the sense that you buy in carload lots from various merchants or producers in various parts of the country and ship the produce into the store in Baltimore and then ship it out locally? Do you get in touch with the man in Texas who has a carload of tomatoes and you sell that carload of tomatoes for him in California and never touch it?

Mr. Waidner. No ; we do not do that business. The kind of business we do is that we have the shipper in Texas, for instance, ship to us, 9 times out of 10 on a consignment basis. In other words, they are still his tomatoes when they arrive in Baltimore. We break the cars and sell them to the buyers who want to buy them.

Representative Thomas. That is a local business?

Mr. Waidner. Exactly. If a man wants to buy 50 crates, or if a man wants to buy 1 crate, he can buy them from us. I will try to point out to you that there is no Federal or State law that can possibly regulate a farmer’s hours during his crop time.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1008]

In other words, if you were going into a farmer’s packing house, or a grower’s or shipper’s packing house during the time he is marketing his crop of cantaloups and attempt to tell him today that he can only work 6 or 7 hours, his tendency would be to call in the riot squad from his local police department, because he knows that the thing that is important is to get the cantaloups, which are highly perishable, on the market as quickly as he possibly can. We follow right in the track of that same system, right from the producing system in one point of the country to another. So it is practically impossible for us to have a period when we are dull, that is, if we want to stay in business, because at the very time they stop shipping the Arizona cantaloups, for instance, we are looking for some other commodity that we can hope to increase our volume with and thereby be able to stay in business.

Another thing that we are confronted with in this particular industry is the fact that it is impossible for us to add these increased costs to the commodity that we have for sale. We deal in apples, we deal in onions and potatoes and right down the line, but actually, gentlemen, we are not dealing at all in those commodities, what we are dealing in is service. I mean that is the thing we are producing. We do not produce the commodities that we sell, but we produce the service. In other words, the man in Texas, or the man m Florida, or wherever he happens to be, wants his stuff marketed on a terminal market and trusts that particular shipment to our care. What we are supposed to do is to find buyers to buy it. It is not a question of us being able to say, “Well, now, since this new Federal law has gone into effect, or since this new local law has gone into effect, from now on we will tack on 10 or 15 cents a package or crate in order to make up the increased cost.” We absolutely cannot do that because we are dealing in perishable commodities. When the cantaloups are at our place of business and if we do not sell them today then 9 times out of 10 tomorrow we will be selling them at a lower price.

Representative Dunn. If you do not get the produce sold for the price you ask what do you do with it?

Mr. Waidner. We sell it at the price that the buyer wants to pay for it.

Representative Dunn. Suppose you do not get a buyer?

Mr. Waidner. Beg pardon?

Representative Dunn. Suppose you do not get a buyer?

Mr. Waidner. Well, of course, if we do not get a buyer we have to seek buyers. We are always seeking them, you know, but eventually, in a situation like that, the produce would be sent to the dump.

Representative Dunn. That is what I would like to find out. I was informed that before they would bring down the prices in Baltimore that they would dump carloads of fruit into the bay.

Mr. Waidner. That might be the case in some rare instances, but I think the general practice is that the majority of the people that are engaged in this line of business do not do that.

Representative Dunn. Do you know if that is a fact?

Mr. Waidner. Beg pardon?

Representative Dunn. Do you know if that is the fact?

Mr. Waidner. I would say offhand that is not a fact.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1009]

Representative Dunn. You do not know that that has ever happened?

Mr. Waidner. No, sir; not at all.

Representative Dunn. I just want to get that information.

Representative Schneider. Who takes the loss?

Mr. Waidner. It depends on the merchandise. There are three people usually involved, the shipper, the man who, in the first instance, has his money tied up in it; then the railroad has the freight charges tied up in it, and the commission merchants, at least some of them, might have advances tied up in it. There may be any one of three people involved in a transaction of that kind, and all three may be involved.

Representative Schneider. To what extent does the original producer become involved in it?

Mr. Waidner. The original producer becomes involved in it to the extent of being responsible for the freight charges, if you can collect the freight charges from him in case any large quantity of his shipment went to the dump, or anything of that kind, but the committee need not be perturbed about anything of that kind happening in the produce business.

The Chairman. You never heard of it?

Mr. Waidner. Beg pardon?

The Chairman. You never heard of it?

Mr. Waidner. I heard of it, undoubtedly.

The Chairman. You know it has happened?

Mr. Waidner. It has happened.

The Chairman. It has happened many times when they have taken cars and dumped them in the East River in New York, has it not?

Mr. Waidner. I do not know, except maybe you read about that in the paper.

The Chairman. Did it or did it not happen?

Mr. Waidner. I do not know whether it happened actually. I only know what I read in the papers about a situation like that. I know it has never happened in the Baltimore market.

The Chairman. You have never known it to happen in Baltimore?

Mr. Waidner. I have never known of a solid carload being dumped in Baltimore.

The Chairman. Have you ever known of parts of a carload being dumped?

Mr. Waidner. Certainly, out of a carload of some particular commodity, for instance, that comes in there might be a question where the commodity was shipped too ripe, or shipped in a broken car.

The Chairman. You do not know of a carload being dumped because they did not get the price for it that they asked? That is the question that has been asked.

Mr. Waidner. That is right.

The Chairman. It has been done frequently, has it not?

Mr. Waidner. I am sure it has not been done frequently, not according to the total business done in Baltimore.

The Chairman. You have done that?

Mr. Waidner. Very seldom.

The Chairman. You say it is not done frequently in comparison to the total amount shipped?

Mr. Waidner. That is it, exactly.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1010]

The Chairman. But you know many cars have been dumped, destroyed, because they could not get the price they wanted?

Mr. Waidner. I could not see how you can say there were many.

The Chairman. How many, if any, have been dumped?

Mr. Waidner. Some have been dumped.

The Chairman. We have adopted the rule not to ask questions during the general statement of the witness, but I did that because I would like to get clear on this point. You testified that you did not know of any of it being dumped, but you do now know that a lot of it has been dumped, do you not?

Mr. Waidner. I do not: no.

The Chairman. An infinitesimal proportion has been dumped?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

The Chairman. They did not have the money to buy it with and therefore it was dumped; is that not true?

Mr. Waidner. It was not a question of whether they had the money, it was a question of where the merchandise was not in fit condition, or else the market was not good enough to the buyers.

The Chairman. What you mean by “the market was not good enough” is that you did not have persons to buy it?

Mr. Waidner. That is it, exactly.

The Chairman. Where was it dumped?

Mr. Waidner. We usually dump it on one of the city dumps when anything like that happens.

The Chairman. Go ahead.

Representative Thomas. I do not quite get your point of view. Do you have any fear that if this act goes into effect it might hurt the farmer by raising the price of his commodity to such an extent that he cannot sell it, or are you interested in this purely from your own business point of view? Are you attempting to express any sentiment in behalf of the farmer?

Mr. Waidner. Only indirectly. Of course, the farmer would undoubtedly be indirectly affected by this if by any chance we would attempt to increase our commission rate in order to make up for the increased costs.

Representative Thomas. The probabilities are, Mr. Waidner, that if anyone is adversely affected by this bill it is going to be the farmer rather than the commission man; is that not a fact?

Mr. Waidner. I agree with you; yes, sir.

Representative Thomas. As a matter of fact you gentlemen do not have anything invested in the merchandise that is shipped to you; you do not pay in advance for it, do you?

Mr. Waidner. Generally, no. I am speaking for myself in that case.

Representative Thomas. When there is a loss taken there is nobody in the world who takes the loss to any greater extent than the farmer?

Mr. Waidner. You are exactly right; yes, sir.

Representative Thomas. As a matter of fact this Congress passed a bill in 1933 called the Produce Shippers Act to remedy an ugly situation that has grown up in this business. In other words, without casting any reflection on any commission merchant, the practice had grown up to a large extent which permitted your business, under some conditions, to literally rob the farmers.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1011]

In other words, it came about like this—and I am speaking from first-hand information, because I had the unfortunate duty of prosecuting some of the concerns in a situation which is exactly like I am going to detail to you: Here is an honest grower down on the Mexican border in Texas; he turns over to the local produce man 50 or 100 carloads of onions, and the produce man does not have a thin dime tied up in the 100 cars, all he has tied up is some telephone bills, perhaps, to the commission merchant down in Texas, and the farmer comes back to the commission merchant in Texas and says, “Now, I want my money.” The commission merchant in Texas says, “Those fellows up in Baltimore skinned me, they will not even pay me for this, they say the onions were rotten and they dumped them, they did not get a dime for them.” The poor farmer writes you and you say, “1 paid Mr. A in Texas.” It ends up with a whole lot of correspondence, and if the farmer tries to sue the merchant in Texas the evidence is in Baltimore and the Texas court has no jurisdiction over your folks in Baltimore; you will not come down and testify. As a matter of fact, the Federal Government had to pass a law taking unto itself jurisdiction in that situation.

The point, after that long-winded discussion, is simply this—that you folks do not have a quarter tied up in the merchandise you receive. If anybody is going to take a loss it is not going to be you boys, it is going to be the farmer. So I do not see tne point in you hollering so loudly and so long.

Mr. Waidner. The point is we have our freight charges tied up in it.

Representative Thomas. You charge that to the producer; that is the first thing you do.

Mr. Waidner. Yes; but you cannot collect.

Representative Thomas. If you cannot collect you are not liable for it either, are you? If I understand you correct, you pay your men from $18 to $22 a week, so you are not going to be affected from the standpoint of the wage. You might be affected a little bit on the hours part. Would not you be willing to help increase the purchasing power in the community in the hope that you might be able to get more customers?

Mr. Waidner. It did not work that way under the N. R. A.

Representative Fitzgerald. The man who preceded you, who represented your industry, claims that in 1933 a survey was made where 2,172 employees out or a total of 9,922 were receiving less than $15 a week and "they were working anywhere from 48 hours a week to as many as 70 hours. Do you think that $15 a week would enable that class of employees to buy strawberries when they first come out, or cantaloups, at the high prices?

Mr. Waidner. I suppose maybe the average of the wage there was perhaps taken over the industry as a whole. I cannot speak for that part of it at all. I mean the only thing I can speak about is what the general average of wages is. for instance, in Baltimore. I know more about- that, than any other particular market.

Representative Fitzgerald. The thing we have to do is help industry as a whole. Here are the figures given out by the previous gentleman, that the workweek was from 48 to 70 hours and the wages of 2.172 employees was less than $15 a week. Do you think at $15 a week a man can maintain himself in not the luxuries but

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1012]

just the necessities of life? Do you think he would be able to buy strawberries at the price you fellows get when they first come out, or perhaps the cantaloupes?

Mr. Waidneb. He perhaps could not.

Representative Wood. Mr. Thomas asked you if you did not feel that you ought to cooperate by reducing the hours of the employees and increasing the purchasing power of the masses in order to bring on better conditions and you said it did not work that way under the N. R. A. How did it work under N. R. A.? What did you mean by that?

Mr. Wacdneb. It simply meant that our cost of doing business was so much increased under the setup that we had at that time that the profits were practically nil. I am speaking again from my own standpoint. I mean I lived up to the letter of the law under the N. R. A.

Representative Wood. What change has there been since the N. R. A.?

Mr. Waidneb. The only change has been that we were able to take off the overtime. That is a tremendous factor, as far as this present bill is concerned. I do not object, and I think the majority of the people in the industry do not object to the minimum wage law, whatever wage law is set up I think will be satisfactory to the majority of the people in the industry, but the thing I am trying to bring before you gentlemen is the fact that this is an industry that will not lend itself to having any particular number of hours set on the industry for any particular workweek.

Representative Wood. What was the position of your business prior to N. R. A., in the years 1931 and 1932? Were you doing a flourishing business then?

Mr. Waidneb. I would not say it was a flourishing business.

Representative Wood. How much business were you doing as compared to now?

Mr. Waidneb. I suppose our total volume was about the same. I mean it ran along level during the N. R. A. years, the same as it did the year before.

Representative Wood. You mean to say that you did not handle any more commodities in 1933 than you aid in 1931 and 1932?

Mr. Waidneb. Perhaps if there has been any increase it has been very small, a very small increase.

Representative Wood. Then you have not reaped any benefit from the present New Deal administration, have you?

Mr. Waidneb. Absolutely not.

Representative Wood. You do not do any more business?

Mr. Waidner. Absolutely not; no, sir.

Representative Wood. What were your profits in 1932 and 1933?

Mr. Waidneb. I do not remember that offhand.

Representative Wood. Did you still make a 10 percent profit at that time?

Mr. Waidner. No ; we did not make a 10 percent profit at that time.

Representative Wood. Did you still make a 7 percent profit?

Mr. Waidner. We did not make 7 percent then.

Representative Wood. How many men did you employ in 1932, in your business?

Mr. Waidner. I do not remember that offhand.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1013]

Representative Wood. You do not remember?

Mr. Waidner. It would be about the same number as I employ now.

Representative Wood. How many?

Mr. Waidner. Seventeen altogether.

Representative Wood. Seventeen?

Mr. Waidner. That includes all employees; yes, sir.

Representative Wood. Did you employ 17 in 1932?

Mr. Waidner. We perhaps did. We might have employed maybe 15.

Representative Wood. Don’t you know how many employees you employed in 1932?

Mr. Waidner. Not offhand; no, sir. It might have been somewhere in that figure.

Representative Wood. It might have been?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. How many hours did you work in 1932? What was your workweek then?

Mr. Waidner. Well, the workweek is more or less determined----

Representative Wood (interposing). What is the maximum workweek?

Mr. Waidner. I should say, speaking of my particular business, that we had a maximum workweek, as far as the produce business in Baltimore is concerned, that had constantly decreased since the time I went in business in 1924.

Representative Wood. What was the workweek in 1932?

Mr. Waidner. I would say between 10 and 11 hours a day was the average.

Representative Wood. Eleven hours was the maximum?

Mr. Waidner. Eleven hours was the maximum.

Representative Wood. What was the average hourly wage of the employees in 1932?

Mr. Waidner. I would say it was lower than it is at the present time.

Representative Wood. How much lower?

Mr. Waidner. Well, we had men working in the store there that we paid from $15 to $18 a week. Truck drivers usually get from $18 to $22.

Representative Wood. You had truck drivers working 11 hours a day for $15 to $18 a week?

Mr. Waidner. The truck drivers worked for $18 to $22 then.

Representative Wood. In 1932?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. And they worked 11 hours a day?

Mr. Waidner. They worked from 10 to 11 hours.

Representative Wood. What was the size of those trucks?

Mr. Waidner. Beg pardon.

Representative Wood. What was the size of the trucks that they operated?

Mr. Waidner. Well, they are Chevrolet trucks.

Representative Wood. How many tons?

Mr. Waidner. The official is a ton and a half.

Representative Wood. What is the maximum tonnage of the truck?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1014]

Mr. Waidner. Well, they hold about 4 tons.

Representative Wood. Four tons?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. You give those men $15 a week for 11 hours work?

Mr. Waidner. I did not say that, sir.

Representative Wood. $15 to $22 for 11 hours’ work?

Mr. Waidner. I say the truck drivers usually got $18 to $22.

Representative Wood. What do they get now?

Mr. Waidner. Now they get around $20 to 22.

Representative Wood. $20 to $22?

Mr. Waidner. Yes, sir.

Representative Wood. No one gets any more than $22. They got $22 in 1932 and still get $22 now?

Mr. Waidner. They may have gotten $18 in 1932.

Representative Wood. Your volume of business is not more now than it was in 1932?

Mr. Waidner. It is not; no, sir.

Representative Wood. Was it any less than it was during the N. R. A.?

Mr. Waidner. The volume of business was not less, but the profits were practically wiped out during the time we had the N. R. A. in effect.

Representative Wood. What do you mean by paying the agents a commission? What do the agents do?

Mr. Waidner. They are supposed to solicit consignors of fruit and vegetables for us.

Representative Wood. Who are the agents?

Mr. Waidner. They are people who perhaps are shippers themselves, engaged in growing or shipping the commodities from the point of origin.

Representative Wood. You said “shippers.” You do not mean the railroads, do you?

Mr. Waidner. No; they are private individuals.

Representative Wood. They are engaged in just shipping on commission or getting the business for you?

Mr. Waidner. That is it exactly; yes, sir.

Representative Wood. How many of those agents have you?

Mr. Waidner. Well, it varies. In other words, we might have one or two.

Representative Wood. How many have you now?

Mr. Waidner. We have about five or six, I should say offhand.

Representative Wood. You have five or six agents?

Mr. Waidner. That is right.

Representative Wood. That covers the business in which you employ 17 people?

Mr. Waidner. That is right, but of course all that business is not gotten by these agents, you know.

Representative Wood. How much business does your firm individually get without the assistance of these agents?

Mr. Waidner. We get practically all of it. That is a change that has taken place in the business.

Representative Wood. What commission do you give the agents for getting the business for you?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1015]

Mr. Waidner. From 2 to 3 percent.

Representative Wood. From 2 to 3 percent?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. Does that come out of the 10 percent?

Mr. Waidner. That does; yes, sir; and thereby drops our net or at least our gross commission for doing business.

Representative Wood. What is the largest commission concern in Baltimore similar to your business?

Mr. Waidner. I should say that there perhaps are two others, Zimmerman Bros, and Stevens Bros.

Representative Wood. How many people do they employ?

Mr. Waidner. I guess they employ about the same number that we do.

Representative Wood. There are no other larger firms in Baltimore, are there?

Mr. Waidner. I think not. I think you will find, in point of volume of business that is done there, that we are within the first five.

Representative Wood. About what is your volume of business annually?

Mr. Waidner. About a half million dollars.

Representative Wood. About a half million dollars?

Mr. Waidner. Yes, sir.

The Chairman. All right, go ahead, Mr. Waidner.

Mr. Waidner. I would like to correct an erroneous impression, perhaps, that you have about the way the commodities are handled. I mean when these commodities come in, you know; I mean we are seeking the market, there is no doubt about that. I mean perhaps your statement there gives the impression that the commission man in general is an inefficient somebody who just stands around, who will not go out to get a customer for the stuff that he will have to, more or less, send to the dump. I mean the competition in this business is such that those people who are able to survive and do an honest business are those who are really efficient.

Representative Thomas. You are right. I have had plenty of experience with them.

Mr. Waidner. In other words, the P. A. C. Act would have a tendency to keep us lined up if nothing else would. We ourselves have been in business since 1885 and we are still doing it.

Representative Wood. You said your profits were practically wiped out during the N. R. A.?

Mr. Waidner. Yes, sir.

Representative Wood. How did that come about? It was not because of your paying more wages, was it?

Mr. Waidner. Certainly it was. That was the whole crux of the situation.

Representative Wood. You paid a few dollars a week more to these employees. Before the N. R. A. you paid $15 to $22, and after the N. R. A. you paid $20 to $22.

Mr. Waidner. If I said $15 to $22 it was wrong, because it should have been from $16 to $22, because they set the minimum in Baltimore at $16. There was nobody paid less than $16.

Representative Wood. How many did they pay $22?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1016]

Mr. Waidner. I do not know that offhand.

Representative Wood. You do not know?

Mr. Waidner. No.

Representative Wood. Do you know anything about the pay roll?

Mr. Waidner. I think I do. I sign the pay-roll checks.

Representative Wood. Do you have a special man to keep track of the 17?

Mr. Waidner. The business is not large enough for that; no, sir.

Representative Wood. What is your position in the firm? Are you the president?

Mr. Waidner. The proprietor; yes, sir.

Representative Wood. You are the proprietor?

Mr. Waidner. Yes, sir.

Representative Wood. You do not know how many men you pay $17 a week?

Mr. Waidner. I can give it to you roughly. I should say there may have been two that we had at that time.

Representative Wood. How many did you pay $22 last week? You had a pay roll last week, did you not?

Mr. Waidner. You mean you want me to give you the present pay roll?

Representative Wood. How many did you pay $22 a week last week, or the week before?

Mr. Waidner. We have only one truck driver that we pay $22 a week.

Representative Wood. Whom else did you pay $22 a week?

Mr. Waidner. We did not pay the other store help $22.

Representative Wood. You paid one man $22?

Mr. Waidner. That is it, exactly; yes

Representative Wood. What did you pay the rest of them?

Mr. Waidner. One man we pay $20 and the others we pay $18.

Representative Wood. $18?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. One you pay $22, one you pay $20, and the rest $18?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. And you paid $16 before N. R. A.

Mr. Waidner. No; after N. R. A. we paid $16. In other words, during the depression, the way the thing worked during the depression, in order to maintain a semblance of a business and try to keep in the business what we did was perhaps—I never paid less than $15 even during the depression.

Representative Wood. I thought you said you had as much business in 1932 as you had in 1933.

Mr. Waidner. I did; yes, sir.

Representative Wood. What was the reason for shifting these men around by juggling the work?

Mr. Waidner. I do not understand you when you say ‘‘juggling the work.”

Representative Wood. You did not stagger the work at any time, did you?

Mr. Waidner. You mean during the N. R. A.?

Representative Wood. Did you stagger the employment in 1932?

Mr. Waidner. During the N. R. A.?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1017]

Representative Wood. Before the N. R. A.

Mr. Waidner. No.

Representative Wood. Did you during N. R. A.?

Mr. Waidner. No; I did not during N. R. A.

Representative Wood. Did you ever stagger your employees?

Mr. Waidner. No.

Representative Wood. You said that there was some arrangement of keeping your employees. What was the reason for it?

Mr. Waidner. During the N. R. A. they set the hour limit and we lifted it up to the hour limit. What we did instead of going ahead and laying off experienced men after they worked 8 hours, or whatever the number of hours was during the week, we paid them time and a half for overtime. In other words, the business is such that you cannot just pick a man out of thin air and tell him to go ahead and do his work. You have got to have some experienced help to do that for you, and of course it takes time to bring the experienced man in.

Representative Wood. According to your testimony you said you paid $16 to $22 a week before N. R. A.

Mr. Waidner. No, sir. I think before the N. R. A. I never paid less than $15 a week.

Representative Wood. $15 to $22?

Mr. Waidner. $15 to $20,1 should say; yes, sir.

Representative Wood. To $20?

Mr. Waidner. Yes.

Representative Wood. Now, you just said you paid 13 employees $18 a week.

Mr. Waidner. No; the 17 that I employ includes the office help, and also the salesman, I mean the porters that are really affected by this. There are seven men who are in the laboring class.

Representative Wood. In regard to the wage-rate adjustment, you had to pay a few dollars more under the 40 hours a week to all those 17? Is that what caused you to not make any profit in 1933?

Mr. Waidner. It was not that; no, sir.

Representative Wood. What was it?

Mr. Waidner. It was the fact of paying time and a half for overtime when we had to work the men 10 and 11 hours a day, and sometimes 12 hours a day.

Representative Wood. You just said you shifted them around to Work 40 hours a week.

Mr. Waidner. No; I did not say that at all. I told you I complied with the hours set under N. R. A., but rather than let the experienced men go off after they worked 8 hours and put on inexperienced men who did not know how to do the work we kept the experienced men on and paid them time and a half.

Representative Wood. What was the gross increase in wages of the 17 employees?

Mr. Waidner. It was not less than 50 percent. As a matter of fact, it was perhaps more than that. We were paying them time and a half for overtime, you see.

Representative Wood. How do you figure that 50 percent increase?

Mr. Waidner. It would be a 50-percent increase. I mean if we paid them for straight time that would be an increase there, and

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1018]

of course with time and a half that would be another 50 percent- added.

Representative Wood. You did not pay any attention to the 40 hours a week, you just worked the men right along 10 and 11 hours a day?

Mr. Waidner. I would not say 10 and 11 hours.

Representative Wood. Did you work any of those 17 employees 40 hours a week during the N. R. A.?

Mr. Waidner. We did not have a 40-hour week established in the fresh fruit and vegetable industry. I think the number of hour's was 50 hours set in our industry.

Representative Wood. That was the code?

Mr. Waidner. Yes; that was the code.

Representative Wood. How many did you work over 50 hours a week?

Mr. Waidner. The majority of them worked over 50 hours a week.

Representative Wood. Then you did not pay any overtime, did you?

Mr. Waidner. Absolutely we paid overtime. I paid the overtime for the time they worked over the 50 hours.

Representative Wood. You just said you did not work over 50 hours a week under the N. R. A. You mean you paid them overtime over the 50 hours?

Mr. Waidner. I say I lived up to the code to work then men 50 hours a week on straight time, but rather than lay them off I would keep the efficient men who were experienced in that line of work and pay them time and a half overtime.

The Chairman. Go ahead, Mr. Waidner.

Mr. Waidner. Another point I would like to bring out is the fact that we cannot charge more than 10 percent commission, because just as soon as we do we run into a situation where the shipper on the other end is constantly looking for another outlet for his shipments, and besides not being able to add some of these increased costs of doing business to the actual merchandise we are selling it is impossible for us to change this rate of commission. Those people who have tried to do it have found that it is impossible to do it and have gone back to the standard commission charge of 10 percent for handling truckload shipments and for local shipments, and 7 percent for handling less than carloads. Mr. Herr has already mentioned that we handled over a period of years about 800,000 carloads of produce, and figuring your minimum truckload movement it would bring that up to a million cars, and I want to tell you gentlemen that out of the 800,000 cars that were handled, that part of it that was handled on consignment was handled on a 7-percent basis, not a 10-percent basis.

Representative Dunn. Did you say 800,000 cars?

Mr. Waidner. That is the figure that we have.

Representative Dunn. Whom do you mean by “we”?

Mr. Waidner. I mean the produce business as a whole.

Representative Dunn. I see. I thought you said that you, a comparatively small producer, or commission man, with 17 employees, handled 800,000 cars.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1019]

Mr. Waidner. It would be impossible for us to handle 800,000 cars; yes, sir, that is, our firm.

The Chairman. Is there anything else, Mr. Waidner?

Mr. Waidner. There is one other thing I would like to say and that is that this produce business is one where the employees are not subject to any labor-saving devices. There is absolutely nothing we can do to put any labor-saving machinery in that will be able to cut down on the total number of employees that we have on the pay roll, the way a good many of these other concerns do.

Furthermore, I would like to state that in the produce line of business, while the hours do seem long, and while, at times, there are times during the year when it is necessary to work a man 10 hours or 11 hours and sometimes 12 hours in order to keep the commodities moving the way they should be moving, that is not the same kind of strenuous and hard labor that people are subjected to, for instance, in the assembly line of automobiles, in an automobile plant, or something of that kind. It is a question of it being healthy work where the men are outdoors. There are periods during the day when the men are standing around for an hour or two waiting to have their next order given to them.

There is one question I would like to be permitted to ask, and that is the question about exempting certain employers. I mean, has that been definitely decided?

The Chairman. It has not.

Mr. Waidner. If it is the plan of the committee to put that in there, what is the reason for doing that, if I may ask that question?

The Chairman. Have you any argument against it? If you do we will be glad to hear it.

Mr. Waidner. The argument I have against it is that in this produce business we depend upon the shippers to send their commodities to us for us to make a living out of it, if we possibly can, and the thing is if you have a salesman on the pavement, or in your employ, he is sooner or later bound to know all of these shippers’ names and the sections from which the commodities come, and if by some chance he happens to leave you, opens up a little place of business next door to you, employs his wife, for instance, as the bookkeeper, and has two sons as the helpers in that store. I just want to bring out to you the kind of competition we have to compete with and to put up with in a situation of that kind.

At the same time he is attempting to get shipments and contacting the shippers that you have had for a number of years, he has all that information before him and uses it as a method or a means of getting business, getting it away from us, and at the same time he is exempt, or would be exempt under this particular Federal law if that exemption for employers is put in the bill.

Representative Jenks. What is your principal objection to this bill?

Mr. Waidner. The principal objection is that this particular industry cannot hope to survive under a limitation of hours as proposed by the committee. It is not a question of us being totally opposed. I do not think there is anybody in the industry who is dead set and opposed to limiting the hours. I mean I would like to do it as much as I possibly could, but we would like to have a Federal law whereby it would be workable in our industry.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1020]

Representative Jenks. Supposing the entire industry would be put on the same basis, I cannot see where it would be any hardship to one if they were all put on the same basis.

Mr. Waidner. Except as I have tried to bring out, it would so tremendously increase the cost of distributing the merchandise that we have to distribute that it would be impossible for us to maintain our present method of doing business, especially in view of the fact that there is no possible way for us to pass this increased cost of doing business to someone else, the way that others have done.

Representative Fitzgerald. Your chief objection is to the number of hours. You do not want any limitation?

Mr. Waidner. I do not say that; no, sir. I do say that if we have a limitation set by the committee or by the law, it should be one that is workable in our industry.

Representative Fitzgerald. You say you do not object to the minimum wage. You said that in your testimony.

Mr. Waidner. That is it exactly; yes, sir.

Representative Fitzgerald. What I gather from your testimony is that you are opposed to the limitation of hours.

Mr. Waidner. I am only opposed to the limitation of hours to the extent that we do not want a limitation in our industry that will put us out of business. Forty hours a week would put us out of business.

Representative Fitzgerald. What would you suggest to be the limit?

Mr. Waidner. Not less than 54 hours a week, which gives us 6 days at 9 hours a day.

Representative Fitzgerald. Of course, you understand that after all the work that has been done in the last several years by the administration, there are still several million people out of employment. How are you going to get these people back into employment if your industry is going to continue to hang onto the 60- and 70-hour week?

Mr. Waidner. I just said I am opposed to 60 or 70 hours. What I would like to see is a 54-hour week established in the industry.

Representative Fitzgerald. Do you think the industry can carry on by reducing from 70 hours to 54 hours a week?

Mr. Waidner. I do not mean to indicate that the industry works 70 hours a week.

Representative Fitzgerald. The testimony given by your representative is that during 1933, when the survey was made, the majority of the full-time employees worked from 48 to 70 hours.

Mr. Waidner. When I first came into the business everybody worked 12 hours a day.

Representative Fitzgerald. What was the average number of hours worked then?

Mr. Waidner. I would say the average at the present time is 10 to 11 hours. It is 10½ in the industry at the present time.

Representative Fitzgerald. You said you are working 11 hours a day, 5¾ days a week in your particular industry.

Mr. Waidner. You asked me what I thought the average was. I am telling you what I think it is in Baltimore, as far as Baltimore is concerned.

Representative Fitzgerald. How many is that?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 1021]

Mr. Waidner. Between 10 and 11.

Representative Fitzgerald. That would be 60 hours a week.

Mr. Waidner. Well, it would be that; yes, sir. I should say 60 hours a week is the correct figure.