———————————————————————————————————————————————————

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

JOINT HEARINGS

BEFORE THE

COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR

UNITED STATES SENATE

AND THE

COMMITTEE ON LABOR

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

SEVENTY-FIFTH CONGRESS

FIRST SESSION

ON

S. 2475 and H. R. 7200

BILLS TO PROVIDE FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF FAIR

LABOR STANDARDS IN EMPLOYMENTS IN AND

AFFECTING INTERSTATE COMMERCE

AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES

PART 2

JUNE 7 TO 15, 1937

Printed for the use of the Committee on

Education and Labor, United 8tatee Senate, and the

Committee on Labor, House of Representatives

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON: 1937

=================================================================================================================================

PAGE II

COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR

United States Senate

United States Senate

HUGO L. BLACK, Alabama, Chairman

ROYAL S. COPELAND, New York

DAVID I. WALSH, Massachusetta

ELBERT D. THOMAS, Utah

JAMES E. MURRAY, Montana

VIC DONAHEY, Ohio

RUSH D. HOLT, West Virginia

CLAUDE PEPPER, Florida

ALLEN J. ELLENDER, Louisiana

JOSH LEE, Oklahoma

WILLIAM E. BORAH, Idaho

ROBERT M. LA FOLLETTE, Jr. Wisconsin

JAMES J. DAVIS, Pennsylvania

Kennbth E. Haigler, Clerk

COMMITTEE ON LABOR

House of Representatives

WILLIAM P. CONNERY, Jr., Chairman, Massachusetts

MARY T. NORTON, New Jeraey

ROBERT RAMSPECK, Georgia

GLENN GRISWOLD, Indiana

KENT E. KELLER, Illinois

MATTHEW A. DUNN, Pennsylvania

REUBEN T. WOOD, Missouri

JENNINGS RANDOLPH, West Virginia

JOHN LESINSKI, Michigan

JAMES H. GILDEA, Pennsylvania

EDWARD W. CURLEY, New York

ALBERT THOMAS, Texas

JOSEPH A. DIXON, Ohio

WILLIAM J. FITZGERALD, Connecticut

WILLIAM F. ALLEN, Delaware

GEORGE J. SCHNEIDER, Wisconsin

SANTIAGO IGLESIAS, Puerto Rico

RICHARD J. WELCH, California

FRED A. HARTLEY, Jr. New Jeraey

W. P. LAMBERT8ON, Kansas

CLYDE H. SMITH, Maine

ARTHUR B. JENKS, New Hampshire

Mart B. Cronin, Clerk

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE III]

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 271]

The joint committee met, pursuant to adjournment, at 10 a. m., in the caucus room, Senate Office Building, Representative Connery presiding.

Present: Senators Hugo L. Black, James E. Murray, Rush D. Holt, Allen J. Ellender, Robert M. La Follette, Jr., and James J. Davis.

Representatives William P. Connery, Robert Ramspeck, Matthew A. Dunn, Reuben T. Wood, Jennings Randolph, Richard J. Welch, Fred A. Hartley, William P. Lambertson, Albert Thomas, Joseph A. Dixon, William F. Allen, and Santiago Iglesias.

Representative Connery. The committee will come to order. Senator Black will be delayed for a few minutes and has asked me to go ahead with the meeting.

This morning we will hear Mr. John L. Lewis, representing the Committee for Industrial Organization and the United Mine Workers of America.

STATEMENT OF JOHN 1. LEWIS, REPRESENTING THE COMMITTEE FOR INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATION AND UNITED MINE WORKERS OF AMERICA

Mr. Lewis. Mr. Chairman and members of the joint committee, I have a brief prepared statement here which should not take me very long to read.

We, of the United Mine Workers of America, and of the Committee for Industrial Organization, wish to pledge our general support to the principle of a minimum wage and maximum workweek as contained in the legislation, Senate bill 2475 of the present Congress, which your committee now has under consideration. In commenting on the bill I shall have some constructive changes or suggestions which I deem vitally important and which I wish to place before you.

The basic reasons which impel us to support these principles of the pending bill are, as follows:

First. It will increase mass purchasing power, which is an essential condition to permanent economic recovery and stable prosperity.

Second. It will, through reduction in hours of work, make way for the employment of hundreds of thousands of industrial workers who are now without work or on relief.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 271]

FAIR LABOR STANDARDS ACT OF 1937

MONDAY, JUNE 7, 1937

The joint committee met, pursuant to adjournment, at 10 a. m., in the caucus room, Senate Office Building, Representative Connery presiding.

Present: Senators Hugo L. Black, James E. Murray, Rush D. Holt, Allen J. Ellender, Robert M. La Follette, Jr., and James J. Davis.

Representatives William P. Connery, Robert Ramspeck, Matthew A. Dunn, Reuben T. Wood, Jennings Randolph, Richard J. Welch, Fred A. Hartley, William P. Lambertson, Albert Thomas, Joseph A. Dixon, William F. Allen, and Santiago Iglesias.

Representative Connery. The committee will come to order. Senator Black will be delayed for a few minutes and has asked me to go ahead with the meeting.

This morning we will hear Mr. John L. Lewis, representing the Committee for Industrial Organization and the United Mine Workers of America.

STATEMENT OF JOHN 1. LEWIS, REPRESENTING THE COMMITTEE FOR INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATION AND UNITED MINE WORKERS OF AMERICA

Mr. Lewis. Mr. Chairman and members of the joint committee, I have a brief prepared statement here which should not take me very long to read.

We, of the United Mine Workers of America, and of the Committee for Industrial Organization, wish to pledge our general support to the principle of a minimum wage and maximum workweek as contained in the legislation, Senate bill 2475 of the present Congress, which your committee now has under consideration. In commenting on the bill I shall have some constructive changes or suggestions which I deem vitally important and which I wish to place before you.

The basic reasons which impel us to support these principles of the pending bill are, as follows:

First. It will increase mass purchasing power, which is an essential condition to permanent economic recovery and stable prosperity.

Second. It will, through reduction in hours of work, make way for the employment of hundreds of thousands of industrial workers who are now without work or on relief.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 272]

Third. From a humanitarian standpoint it will bring a greater measure of leisure and economic well-being. It will mean at least a glimmer of sunlight to millions of submerged American workers who now live in economic darkness and despair.

Fourth. From the viewpoint of industrial democracy the pending measure will offer to these unfortunate victims of our existing economic system an opportunity to rise to industrial citizenship or, in other words, a chance through unionization to attain to collective bargaining with their employers and thus achieve industrial emancipation.

We are fully conscious of the fact that this bill is the first approach to the problem of extending the protection of the Federal Government to that submerged group of citizens who are the most distressed victims of commercial exploitation.

DEFINITE STANDARDS RECOMMENDED

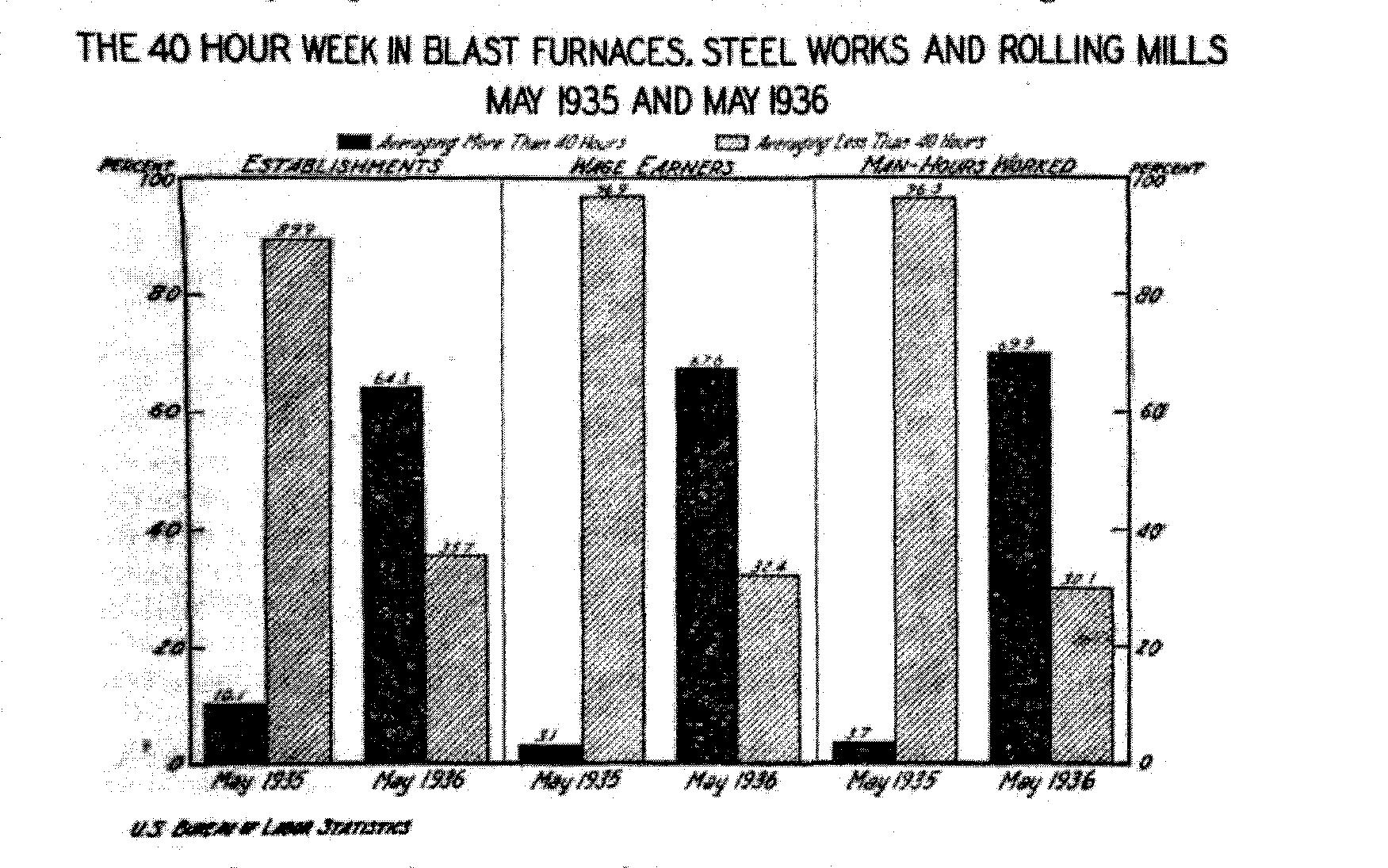

It is unnecessary to state that before its enactment, definite standards as to minimum rates of pay and maximum hours of work should be incorporated in the present bill. My recommendation as to rates of pay is a minimum of 40 cents per hour. As to hours of work, the standard in my opinion should be 5 days of 7 hours each or 35 hours per week, with authority granted to the Board to expand to a 40-hour maximum, or to reduce to a 30-hour maximum, when the Board’s investigations reveal that a 30-hour maximum workweek in specific industries is practicable, or, on the other hand, where a 40-hour workweek would appear to be temporarily necessary.

Under these conditions the standard weekly wage, regardless of sex, would be $14, which should also obtain for the 30-hour week, and be increased to $16 for the 40-hour weekly maximum.

Personally, I am a firm believer in the practicability, under proper industrial policy and control, of a 30-hour workweek. My own organization, the United Mine Workers of America, was the pioneer proponent of a 6-hour workday and a 30-hour workweek. During the past 4 years both branches of the coal industry—anthracite and bituminous—have through collective bargaining reduced maximum weekly hours of work from 48 to 35 hours, a decline of 32 percent.

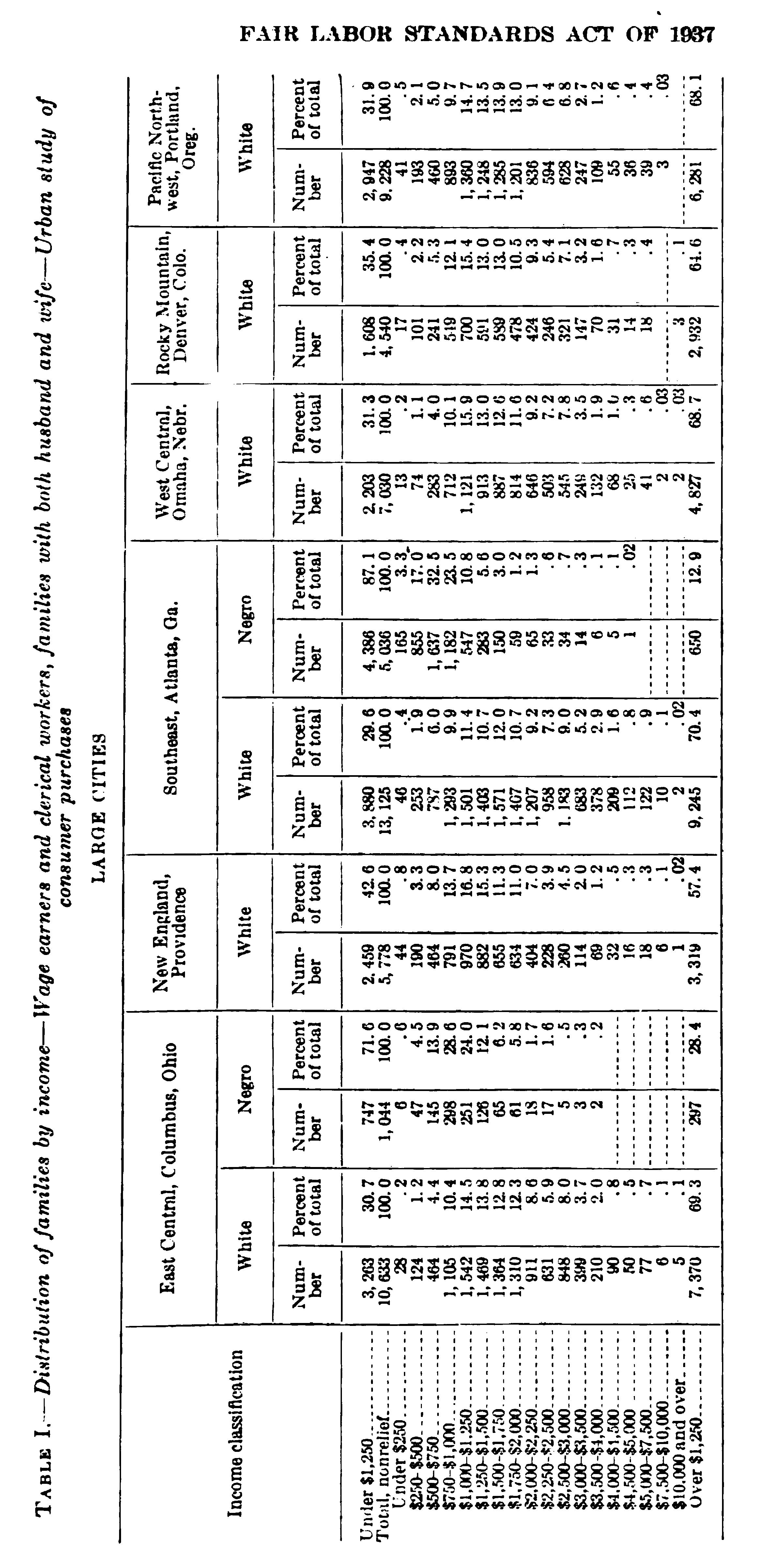

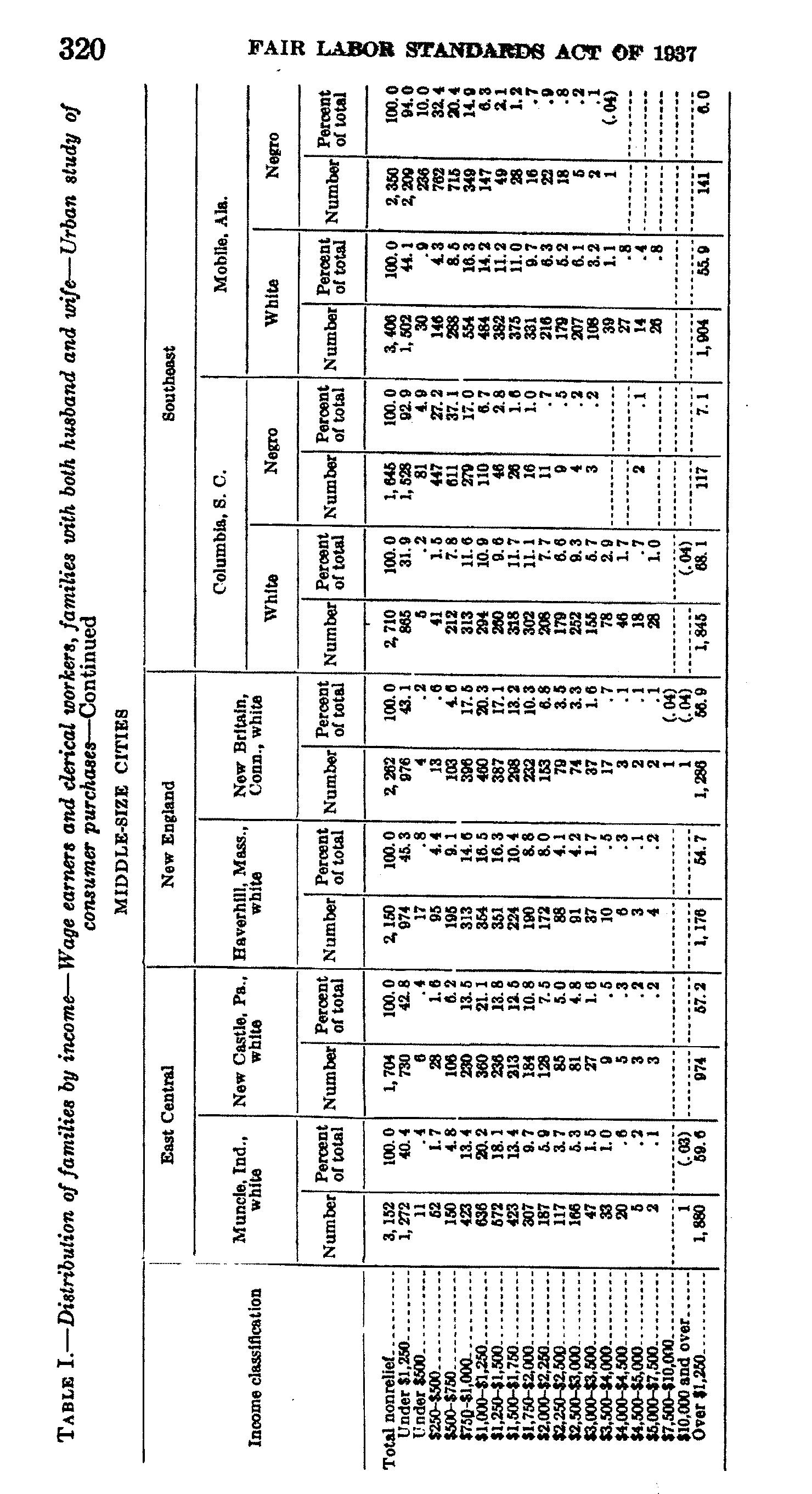

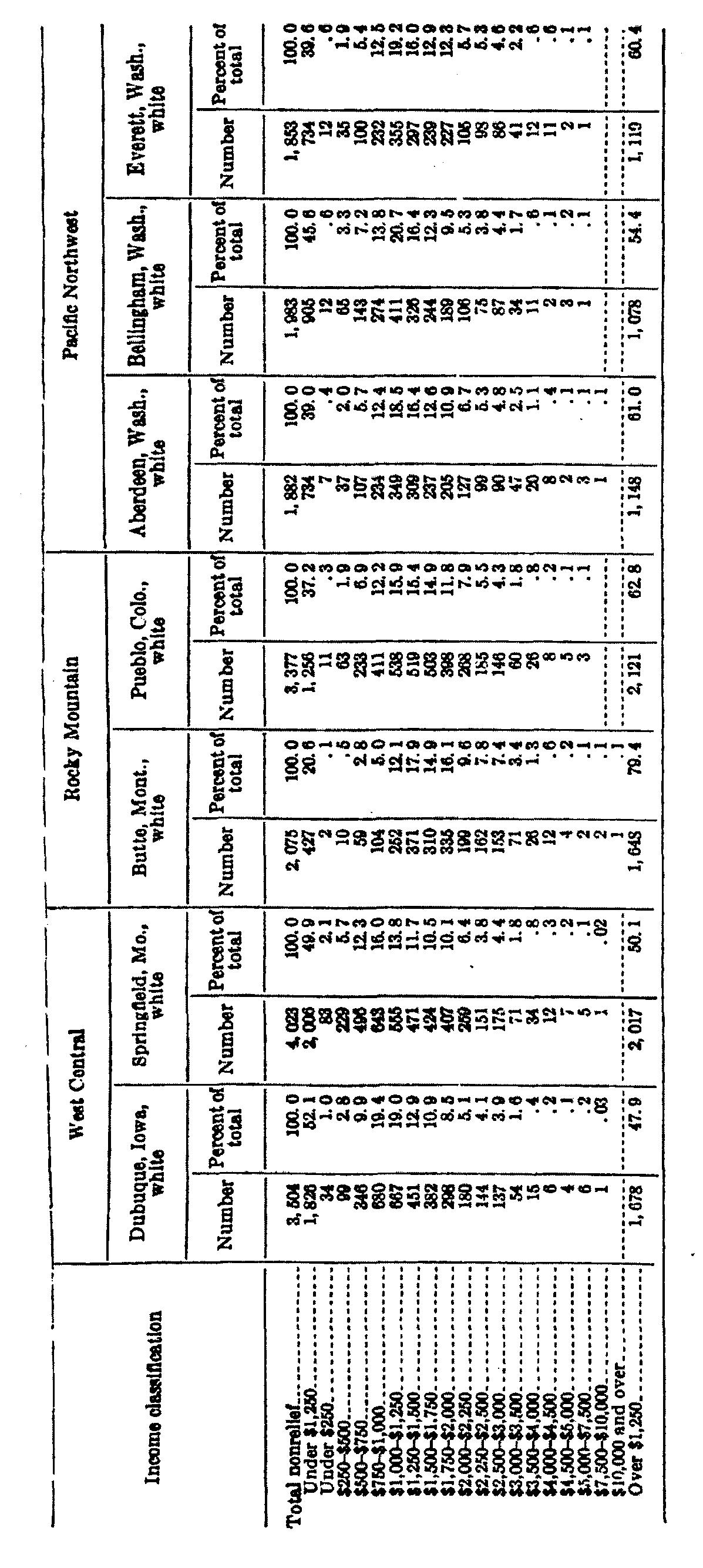

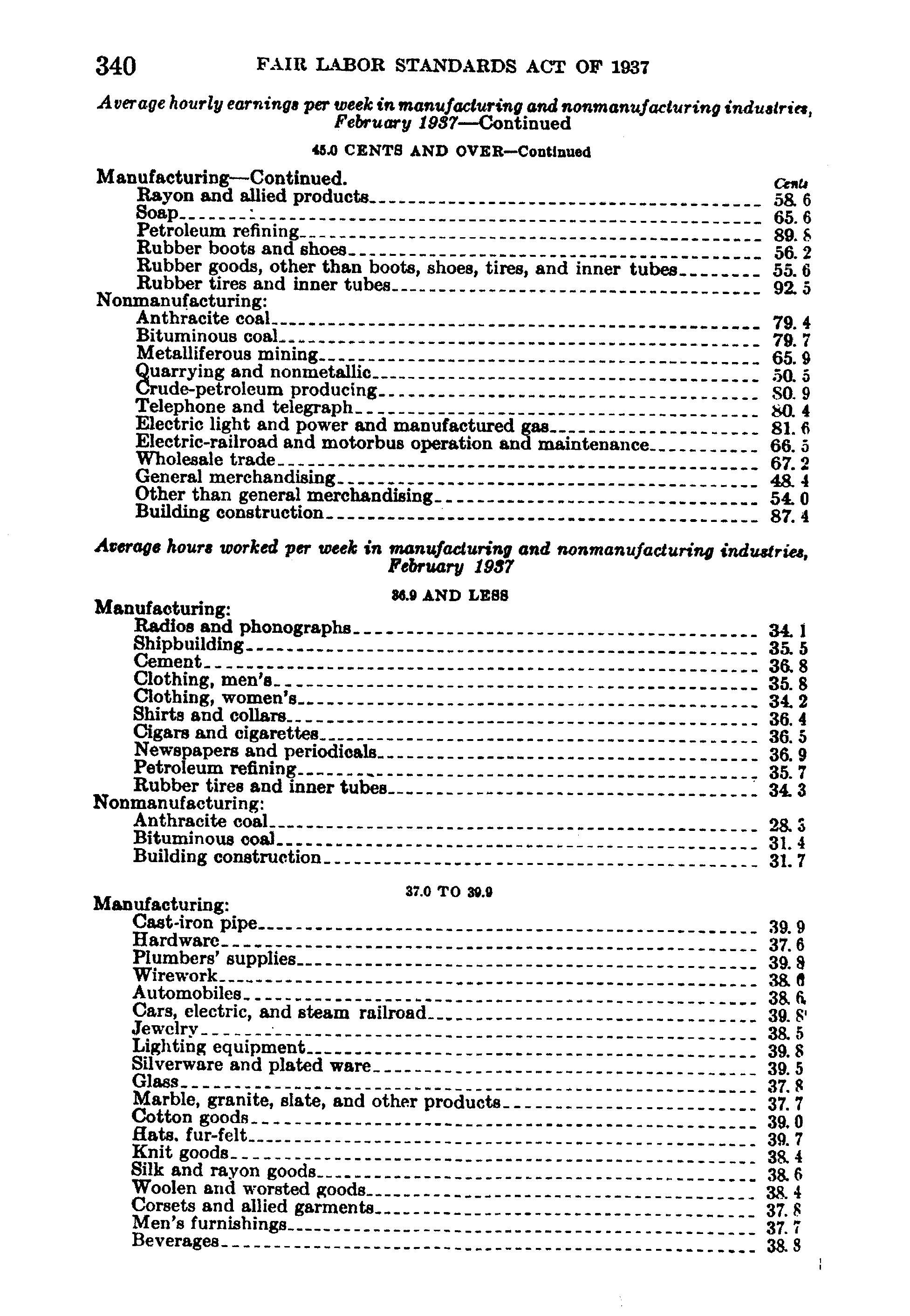

GEOGRAPHICAL DIFFERENTIALS

I am firmly opposed to wage differentials based on geography. Usually this is no more than a plea for the continuance of low living standards in the Southern States,. Such a differential has absolutely no justification. Its proposal is based on an alleged difference in cost of living between the North and the South. I maintain that this is pure allegation. There is not a scrap of evidence to support such a statement. Indeed, so far as data are available, they indicate that the prices of the various items in a family budget are, by and large, just as high in the South as in the North.

Of course, it is a matter of common knowledge that the standard of living of the average southern wage earner, particularly the cottonmill worker, is somewhat lower than that of the northern wage earner. This is so because wage scales on the whole are lower in the South, and in consequence the southern worker has less money to spend. The difference, in other words, is due not to the fact that prices of individual commodities are lower in the South, but simply to the fact that, be

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 273]

because of this lower income, the southern worker gets fewer of the good things of life.

His food may cost him less, but that is because he gets less milk, less fresh vegetables and fruits, and less fresh meats. His housing may cost less, but that is because he gets an inferior type of housing.

Certainly the Government cannot put its approval upon this unfortunate condition. The southern worker is entitled to as good a standard of living as the northern worker. And, if the standard is to be the same, I reiterate, there is absolutely no ground for believing that its cost would be less in the South than m the North.

SECTION 5 OF THE ACT AND ALL PROVISIONS RELATING THERETO SHOULD BE ELIMINATED

As to changes in the bill, I wish to say that in my judgment the pending legislation would be greatly simplified and more satisfactory if section 5 of the bill and other provisions connected therewith should be eliminated.

In its fundamental aspects and sanctions the pending bill, in my opinion, is really an extension in principle of the Wagner Act, which guarantees to labor the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of its own choosing. While an infringement of this right is defined by the WTagner Act as “an unfair labor practice”, as a matter of fact its sanction goes much deeper. It marks the beginning of an industrial bill of rights for workers as against industry, just as the so-called Bill of Rights in our political Constitution guarantees personal and civil liberties of the citizen or individual as against our State or Federal Governments. They safeguard the freedom of the citizen against arbitrary or tyrannical governmental action.

Similarly, the Wagner Act protects industrial workers as citizens of industry against arbitrary encroachments upon their freedom of association and action. They are assured the right of organization and representation in the determination of their compensation and working conditions.

The pending bill, as I stated, builds up or extends the industrial bill of rights inaugurated by the Wagner Act. It declares it to be a matter of public policy that, (1) no “oppressive wage” or wage below a designated “minimum wage standard” shall be paid by industry; (2) that no “oppressive workweek” above a designated “workweek standard” shall be established; (3) it prohibits as further “oppressive labor practices” the employment of strikebreakers or labor spies by industry; (4) it prohibits industry from employing any children under 16 years of age, or children between 16 and 18 years in hazardous or unhealthy occupations. In other words, the bill under discussion adds four more safeguards to employees as against industry, to the industrial bill of rights founded, as it were, by the Wagner Labor Relations Act. This is as it should be, and the organized-labor movement is profoundly grateful for these fundamental, constructive proposals.

In this connection, I also wish to say that Secretary Perkins in her testimony suggested a further industrial right, which I believe the committee should add to the bill, namely, that women doing the same work as men should receive the same pay as men.

Unfortunately, however, the pending bill, instead of setting up one “standard” or “right” as to minimum wages, provides for two standards,

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 274]

or, in other words, it provides two methods of establishing minimum wage rates, designated respectively “the minimum wage standard” (sec. 2 (10)), and “a minimum fair wage” (sec. 5 (a)), the first beig 40 cents an hour or approximately $800 per annum (50 weeks of 40 hours each), and the second covering a range, subject to the Labor Standards Board, from 40 to 60 cents an hour or maximum yearly earnings of $1,200.

The first or real minimum is based on a straight-out declaration that no employer in industries engaged in interstate commerce shall pay any employee less than 40 cents an hour. Expressed reversely it means that all adult workers are guaranteed the right as against industry, to receive 40 cents per hour. Such a standard is simple, clear, and easy of application by an administrative board.

The second standard set forth in this bill, or “a minimum fair wage’’, is defined as “a wage fairly and reasonably commensurate with the value of the service or class of service rendered.” It must needs be fixed by exhaustive investigation and administrative or judicial determination and after the Board has been advised by the parties in interest. It was perhaps intended to be a step forward from the “minimum- wage standard” in order to cover semiskilled or skilled workers, but | unfortunately it sets up standards that disclose it to be a wage-fixing measure.

The worker does not receive such a wage as a fundamental right which he can invoke against the employer. It can only be established by the Labor Standards Board whenever the Board shall have reason to believe that—

owing to the inadequacy or ineffectiveness of the facilities for collective bargaining, wages lower than a minimum fair wage are paid to employees in any occupation.

Manifestly the bill does not intend to lay down the principle that a minimum wage of 40 cents an hour is the right of employees, but should employees be not effective in collective bargaining or cooperation with their employers, the law, after proper investigation, will guarantee to such employees 20 cents more per hour, or approximately 60 cents per hour or $1,200 per annum. In reality, what is apparently intended by the bill is to set up two standards or minima of compensation to low-paid workers, the first as a general right and the second on an equivalent monetary payment for services rendered, to be determined by the Board through investigation after it has previously investigated the status of collective bargaining in any occupation and declared it to be inadequate or ineffective. It may be that the intent is the laudable one, based on British and Canadian experience, to require all workers in an occupation or industry to conform to the wage standards established by a substantial majority of workers in an industry.

Be this as it may, such a procedure, to say the least, is very confusing and extremely difficult of application. Moreover, what is of fundamental importance is that it is not in accord with American precedent or practice for, I repeat, it amounts to a wage-fixing by a governmental agency made in consideration of all the equities involved.

The history of all attempts to establish minimum wages in America are based on an estimate of the cost to single or married workers of providing themselves with food, shelter, and clothing essential to bare

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 275]

physical needs at least or, in a higher sense, to a standard of living for themselves and their families embodying elements of decency and comfort necessary to the proper performance of social and political activities in a self-governing republic.

Scientific budgetary studies have been involved to ascertain the costs of such standards. The lowest are usually designated as “subsistence”, “living wage”, “health and comfort”, and so forth.

The right of the marginal or unskilled to enjoy such standards is generally accepted in the United States as a matter of public policy.

The method of application is simple. The unskilled workers or those in the lowest grade of the scale of occupations in an industry are entitled to receive the subsistence or living wage, and above this guaranteed minimum, semiskilled or skilled employees are paid differentials established by precedent or through collective bargaining, based on skill, experience, and productivity and hazard.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE LIVING WAGE

It is rather a sad commentary on American wage rates to say that no matter how low a minimum may be established, it will benefit great numbers of workers. For instance, suppose that the irreducible minimum wage rate is placed at 40 cents an hour such as provided in the pending bill, and the maximum working week placed at 35 hours. This would mean, under the assumption of steady employment, weekly earnings of $14, monthly earnings of about $60, and annual earnings—on the basis of 50 weeks of employment—of about $700. A wage scale such as this would be of material benefit to hundreds of thousands possibly even millions of American workers. For this reason I regard the adoption of such a minimum standard as provided by this bill as a most desirable step forward. It may be that at the present time, and in view of all the circumstances, even such a short step as this is all that is practicable.

But I think it would be a calamity if such a wage minimum as that referred to should in any way be construed as a living wage. The labor movement with which I am associated is interested in securing for every American unskilled or semiskilled worker a living wage— that is to say, a minimum income upon which he can maintain himself and his family at a level of healthy and decent living. The skilled worker should, of course, receive a higher wage in accordance with his skill and training. But every worker, no matter how humble his job, should be able to secure at least the essentials of what, for lack of a better term, we may term an American standard of living.

Nor should this wage be set by the standards in those industries in which a “family wage” prevails. It is possible, for instance, that a cotton-mill family, in which the husband, the wife, and say three adolescent children, are all employed in the mill, may obtain a very good income by their combined efforts. But this practice is destructive to all that we cherish most in our American institutions. Normally, a husband and father should be able to earn enough to support his family. This does not mean, of course, that I am opposed to the employment of women, or even of wives, when this is the result of their own free choice. But I am violently opposed to a system which by degrading the earnings of adult males, makes it economically necessary for wives and children to become supplementary wage earners, and then says, “See the nice income of this family.”

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 276]

For these reasons we must keep fighting for the principle of a real living wage. Nor is such a conception the nebulous thing that certain of its opponents would have one believe. On the contrary, the principle of the living wage has been quite generally accepted. Moreover, a series of studies by responsible public and other authorities of the amount of income necessary for a living wage has placed the subject on a factual basis. We now know, with sufficient accuracy for practical purposes, the approximate income which an individual or a family must have in order to maintain what may be described as a minimum standard of living for American wage workers.

This subject was gone into quite thoroughly by the United Mine Workers of America in their appearance before the United States Anthracite and Bituminous Coal Commissions of 1920, the Senate Committee on Manufactures in 1921, the Anthracite Board of Reference in December 1932, and before the National Recovery Administration in 1933 in connection with the Bituminous Coal Code then under discussion.

In this connection, it is my firm belief that we must hold to American tradition and precedent, and accept, as a basis of procedure, the fundamental principle or industrial right upon which precedent and procedure are based. This principle is that every worker should be protected by a minimum wage. Public policy has already sanctioned this standard or right through national and State action and through the decisions of impartial arbitration boards extending from the World War to the present day.

I, therefore, recommend that section 5, relative to "a minimum fair wage” and related sections be dropped from the act. Furthermore, as a representative of the United Mine Workers and the C. I. O., I wish to say that we are willing to stand, as a beginning, upon the “minimum wage standard” of 40 cents per hour.

We should adhere, I am convinced, to the minimum, basic wage as a fundamental right of employees, and not confuse or impede progress by experiments in wage fixing as such.

It is unnecessary for me to add further that it is my conviction also that any sanction for action by the Labor Standards Board such as “the inadequacies or the ineffectiveness of the facilities for collective bargaining”, as set forth in section 5, as a basis for establishing a “minimum fair wage” would be futile. Moreover, in my judgment, it would inevitably bring the administration of the bill into an unfortunate conflict with the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and, in this connection, I suggest that there should be an express provision in the bill that nothing therein contained shall be held to repeal, amend, or modify the National Labor Relations Act or any of its provisions.

ASPIRATIONS OF LABOR

I have emphasized this matter of a living wage and the elimination of section 5 and related sections, because I think it is essential that the bill now being considered be looked at not as an isolated piece of legislation but as one item in a much larger program which is being developed in this country partly through legislation, partly through a developing social consciousness, and partly through the activities of organized labor itself. This bill with its particular proposals will be successful only in the degree in which it fits into the larger program, and this program, in turn, will be successful only

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 277]

in the degree in which it meets the legitimate aspirations of labor. For this reason I think it is entirely pertinent and appropriate at this time to call attention to certain of these aspirations.

WHY LABOR IS ORGANIZING

The lack of understanding among the privileged and sequestered groups of our people as to the spontaneous upswing of labor today toward organization and collective, cooperative, constructive action is indeed one of the most deplorable aspects of contemporary American life. It is forgotten that our industrial workers of today—both young and old—were witnesses to the best, but entirely unsatisfactory, accomplishments of our industrial and financial system under the most favorable auspices of the late twenties. It is also forgotten that a large proportion of present-day workers experienced most disastrously the effects of the collapse of our much-vaunted financial and industrial structure in the year 1929. Furthermore, it is not realized that during the long years of depression which followed, some of our most eminent economists and analysists constantly, through periodicals and the daily press, entertained these same workers by taking our capitalistic system apart and putting it together again, for the purpose of showing its fundamental weaknesses in structure and objectives. And finally today, after these unprecedented opportunities for acquiring first-hand as well as secondary knowledge, our industrial workers are forced, by contemporary developments, to the conclusion that American industrial leadership has not grown in knowledge and wisdom and has nothing more to offer than a repetition of our deplorable experiences of the late twenties.

American labor has always believed that political democracy is a splendid thing. It now knows, therefore, from bitter experience and education that unless it is intelligently united with industrial democracy it will turn to ashes in its hand. Labor has, therefore, decided that our political institutions must be supplemented by sound measures of industrial democracy.

To do this, American workmen are convinced that they must have both political and economic organization and power. They believe their economic strength must be equal in bargaining power with the industrialists so that, through constructive collective bargaining or cooperation with enlightened capital, a stable and permanent prosperity for all groups in America may be secured.

The workers are also convinced that political strength is necessary so that industrial planning under Federal auspices may be made possible. They know that modern industries must be coordinated and correlated; that our objectives must be those of maximum productivity, not of restriction and monopoly; that the main emphasis must not be placed upon high prices and profits but upon low profits and low prices per unit of output and upon a constantly increasing mass income and a constant reduction in hours of work, together with complete reemployment of workers of all classifications who are able and willing to work.

It is for this reason that we feel that the minimum-wage and maximum-hour provisions of this bill are a modest beginning of genuine planning toward a better economic order.

Representative Connery. Senator La Follette.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 278]

Senator La. Follette. Mr. Lewis, in connection with your suggestion for the elimination of section 5 and related provisions of the bill, I would like to call your attention to section 23 (a) and (b) on page 40 of the Senate bill, which reads:

Nothing in thia act, or in any regulation or order thereunder, shall be construed to interfere with or impede or diminish in any way the right of employees to self-organization; to form, join, or assist labor organization; to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing; and to engage in all concerted activities allowed by the law of the land, and the act shall be construed and applied to encourage and protect the self-organization of employees for the purpose of collective bargaining and mutual aid.

(b) Nothing in this act, or in any regulation or order thereunder, shall be construed to invalidate any contract, understanding, or collective-bargaining agreement whereby an employer undertakes to pay a wage in excess of the applicable minimum wage under this act or to require a shorter workweek than the applicable maximum workweek under this act or otherwise to confer benefits or advantages upon employees not required by this act.

Now, it is my understanding that section 5, or one of the purposes of the insertion of section 5 in the act—and if I am mistaken I would like to be corrected by the author of the bill—was for the purpose of meeting tne situation where you might find an agreement entered into ostensibly on the basis of collective bargaining, which might be below the minimum established, and therefore would give the Board the power to look back of that agreement and to ascertain whether or not it had been entered into under effective and bona fide collective- bargaining processes, and to take care of those situations, if there be any such, that might arise whereby an ostensible collective-bargaining agreement might prevail in a certain plant or a certain section of an industry which would not be bona fide in character and would tend under section 23 to prevent the Board from meeting the situation where a spurious agreement or one which had been entered into without bona fide or effective bargaining should tend to prevent the minimum from being established in that particular section or segment of the industry.

Mr. Lewis. If section 5 were to be accepted by the Congress and continued in the act, I would find myself quite in harmony with that provision which you have analyzed. I believe quite definitely that if that standard were set up and this machinery saved for the bill, any contract below that standard should be set aside.

Senator La Follette. That was the point I was coming to, Mr. Lewis. If section 5 were to be eliminated, would there not be danger under section 23, which as I understand it, is for the purpose of permitting the self-organization and collective bargaining and so-called industrial democratic processes to determine wherever it is effective and to prevent the Board from entering the field and disturbing bona fide collective-bargaining activities between employer and employee. Would it not be necessary, if section 5 were to be eliminated, to in some way provide the Board with power to look back of the agreement and make certain that it was not being used for the purpose of breaking down the maximum standard to be established by the Board?

Mr. Lewis. In my opinion, such a provision would not be necessary if section 5 were eliminated because then the bill would simply establish the minimum wage of the various classifications at the suggested rate of 40 cents an hour based on the workweek that would be fixed. And collective bargaining would then have an opportunity to perform its function over and above that minimum.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 279]

I really think that the number of instances where, through collective bargaining processes, indefensible agreements might be made would be relatively few and would be the exception rather than the rule.

My objection to section 5 is based upon a little more broad premise. I think that section 5 would permit wage fixing as such, and that the four standards set forth in the section as being the factors to be considered by the wage-fixing board would result in the fixation of what would be called a fair minimum wage, and that rate, whatever it may be, whatever the finding of the Board, might come to be regarded by the public, by the Government, and by practically everyone as being a fair wage, a proper wage, a justifiable wage, and practically a legal wage.

Senator La Follette. Well, to phrase my question in another way, Do you or do you not see the need of some provision in the bill which will accomplish the objective which I assume that the authors of the measure had in mind when they incorporated section 5, and related sections thereto, in the measure?

Mr. Lewis. You mean should there be a provision in the bill to permit analysis and setting aside of what might be termed subnormal contract on the part of a labor organization?

Senator La Follette. Providing it falls below the minimum of 40 cents an hour, let us say, if that is established, or if it has a provision in it for maximum hours higher than those fixed in the bill.

Mr. Lewis. If the Congress should enact this bill and fix the 40 cents as the minimum, and whatever hours it fixes as the maximum, I would have no personal objection at all to having the Board given the authority to examine into any collective-bargaining agreements below those standards, with authority to modify those agreements if they found it justified. My objection, however, to section 5, does not run to the fixation of this minimum wage of 40 cents. It runs to the question of the determining of this fair minimum wage by the Board in consideration of the four factors or elements set forth in section 5 which, when published and decreed, would be accepted by the public at large and by industry and perhaps by the court as being a fair wage and a legal wage.

Senator La Follette. I understood the basis of your criticism of it from your opening statement, but I wanted to get clearly your feeling as to whether or not there was not a need for a consideration by this committee and incorporation in the bill eventually before it is reported of some provision which will take care of what I understand to be the objective of section 5, namely, to prevent ineffective collective-bargaining agreements or spurious collective-bargaining agreements between employer and employee from pulling a section or segment of industry or a particular industry below the minimum standards fixed by the Board.

Mr. Lewis. Well, I understand if section 5 is eliminated the bill would be much simplified. The work and the powers of the commission would be substantially restricted, that is its administrative work would be relatively simple. That is, if the minimum of 40 cents was fixed for all industries affected by the act there would be no objection at all on my part to having the Board given authority to examine into and modify, if it is necessary, any collective-bargaining agreement made with an employer below the 40 cents an hour standard or the 35 hours I suggest, or whatever the Congress may decide.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 280]

Senator La Follette. It is my understanding that that was the objective of section 5.

Mr. Lewis. You do not mean that is the sole objective, Senator, of section 5?

Senator La Follette. I gathered, largely from the testimony that has been given here, and from questions which have been advanced by the authors of the bill, I understood that that was the primary objective, to meet that kind of a situation, especially in view of die intended objective of the activities of this Board under this law, that they should not invade the field where collective bargaining is effective as provided in section 23 (a) and (b).

Mr. Lewis. As I read the bill, Senator, that function is only an incidental function and a relatively unimportant function as compared with the major powers conferred on the Board under section 5. Section 5 gives the Board authority to set up entirely different wage standards from the minimum wage standard which is set forth in the other sections of the bill, and gives it authority to examine into those conditions, either on their own motion or on complaint of interested parties, and, after considering the equities, to fix a wage for that industry or plant.

Senator La Follette. But may I call your attention to the fact that both sections (a) and (b) of section 5 begin with the sentence, “Whenever the Board shall have reason to believe that owing to the inadequacy or ineffectiveness of facilities for collective bargaining, and wages below a minimum fair wage”, et cetera. Each one of those sections is limited by this opening phrase, and it was my understanding that the purpose of this section was to meet the situation where the Board had reason to believe that an agreement had been entered into where, as it phrased it, owing to the inadequacy or ineffectiveness of the collective bargaining, a situation had been created which produced wages below the minimum.

Mr. Lewis. Well, Senator, if you will pardon me, would that not include all industries in which the workers were not organized? All unorganized industries would come within that category, would they not?

Senator La Follette. Well, it would give the Board authority and power, wherever they believed that collective bargaining had resulted in the establishment of a contract which was below the minimum, to go in and look back of it, if you read section 5 in conjunction with section 23 which prohibits the Board from taking any action which is going to upset a bona-fide collective-bargaining agreement, because as I understand it—I do not want to take any more time than I have taken, and I have taken more than my share now—but as I understand it, the objective of this bill as outlined in section 23, one of them is to prevent the Board from going in and upsetting collective-bargaining agreements or entering the field where collective bargaining is actually functioning in a bona-fide manner, and thereby producing the result of the action of the employer and employee represented by genuine and effective labor organization.

Mr. Lewis. I agree they have that power under the proposal here, but I also think that the Board would have the power to enter into an industry or an area or a field where there was no organization of any character and no collective-bargaining contracts in existence and, on their own motion or upon complaint, undertake to fix in that industry a fair and minimum wage. The Board would have that authority.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 281]

Senator La Follette. Assuming, however, that the purpose is as I have suggested in my question, you do recognize the necessity, do you not, and I think you have already indicated that you would not object or interpose any reasons for the bill providing a power on the part of the Board to look back of the collective-bargaining agreements and to ascertain their bona fide and effective character in cases where there shall be, as a result of contracts, wages which are below the minimum and hours above the maximum.

Mr. Lewis. My attitude toward that is negative. I do not think the Board should have that power in any broad sense. I said that if the Congress fixed the minimum at 40 cents in this bill, and section 5 were eliminated, I would have no objection whatsoever to the Board investigating any collective-bargaining contract which provided for lower than 40 cents or higher than the maximum hours, but I would not grant the Board the authority to fix that rate at 60 cents or 70 cents or 80 cents. Their power should be restricted to making those standards come up to the minimum standards declared necessary by Congress.

For instance, frankly I would not want this bill to convey power to a board to order an investigation into all of the wage agreements in the mining industry right now, or to give the board power to decide that the collective-bargaining agreements in the mining industry were not sound, not proper, were confiscatory, or not in harmony with the facts of the industry, and order a modification thereof. I think the power of the Board should be limited to cases which run below the level of the standards fixed by Congress. I see endless confusion in the adoption of section 5 now. I see a drift toward the complete fixation of wages in all industry by governmental action.

Senator La Follette. But if I understand you correctly, you would not object to the Board having the power in the case of collective-bargaining agreement being reached which was below the minimum so far as wages, or hours in excess of the maximum, of having power to step in and examine that particular agreement and to take action and to lift the agreement-----

Mr. Lewis (interposing). To the standard declared by Congress?

Senator La Follette. Yes.

Mr. Lewis. Now, in other words, if the United Mine Workers of America made an agreement on hours below the 35 or 40 declared by Congress as the standard, or on wages below the 40 cents declared by Congress as the standard, I would be very glad to have the Board come in and bring it up to that standard, but I would not want the Board to have the power to determine what a fair minimum wage for that industry may be, or for a section of that industry, and fix it at 70 or 80 or 90 cents, because that would destroy the efficiency of our collective bargaining and our voluntary action in the coal industry.

Senator La Follette. I think I understand your position.

Representative Connery. Mr. Jenks of New Hampshire.

Representative Jenks. I was not here to hear Mr. Lewis’ statement. There is only one thing I would like to ask. I assume, and I presume that you do, that the object of this bill is to raise the general standard of wages and to lower the hours of labor.

Mr. Lewis. That is right.

Representative Jenks. And do you feel that that is going to materially increase the cost to the consumer?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 282]

Mr. Lewis. I think that this bill, in the manner that I suggest it be amended, would have a very inconsequential effect on costs.

Representative Jenks. For what reason?

Mr. Lewis. Well, because the amount of the increase is so modest, and I really think that the advantage would accrue to the consumers in the entire population by raising wage standards in certain areas, | and increasing the purchasing power of those people.

Representative Jenks. Do you favor including farm labor in this I bill?

Mr. Lewis. I favor including everything which comes under the legal theory on which this bill is prepared; in other words, all of those industries operating in interstate commerce are affected to the degree permissible by the court decisions.

Representative Jenks. Do you believe in carrying this point in industry without any limit to the number of employees?

Mr. Lewis. I think, frankly, that anyone who comes within the purview of the act should be covered by the act, regardless of the number of employees that he may have in his establishment.

Representative Jenks. Even though it might be as low as one employee?

Mr. Lewis. Yes. I see no reason to exempt one man merely because he is one, if he is covered by the act in its legal application.

Representative Jenks. Do you believe that the Board that is to administer this act should be larger or smaller, or do you think that a board of five that the bill calls for would probably be the best working board?

Mr. Lewis. Five is ample in my judgment. I think conceivably a board of three might do it.

Representative Jenks. That is all.

Mr. Lewis. I might say with respect to this cost item, if you would permit me just a further observation, that there are a great many industries in which I think the 40-cent minimum would not greatly increase the wages of the employees. My own idea of the industries in the South is that it would possibly be an increase from an average of now perhaps 32 cents an hour to 40 cents. That is about the range of the cost expansion.

Representative Connery. Mr. Dixon?

Representative Dixon. I yield.

Representative Connery. Mr. Griswold of Indiana.

Representative Griswold. Like Mr. Jenks, Mr. Lewis, I did not hear the first part of your statement, but I am principally interested in this bill for any effect it might have on existing legislation such as the Wagner Labor Relations Act and the Guffey Coal Act, so-called. If you will recall, in this bill it provides that the singular shall be the plural and the plural the singular, and in section 25 of the bill it provides there that an individual, which under the definitions of the bill would allow an individual to appeal, what in your opinion would be the effect if the United Mine Workers or even an unorganized group would comply with all of the provisions of the Wagner Labor Disputes Act, and under this provision had gone ahead and bargained collectively, and then under the definitions of this bill, whether or not one individual could not go in and attack that agreement arrived at under the Wagner Labor Disputes Act?

Mr. Lewis. Perhaps before you came in, I stressed that very point. I stated that in my judgment this section 5 would inevitably bring

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 283]

the administration of the bill into an unfortunate conflict with the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and in this connection I suggest that there should be an express provision in this bill that nothing therein contained should be held to repeal, amend, or modify the National Labor Relations Act or any of its provisions.

Representative Griswold. I brought this out because I brought the same matter up with Mr. Jackson the other day.

Mr. Lewis. I think there should be an express saving clause that would protect that situation. I think that the Wagner Labor Act by all means should remain intact, and that section 5 of this bill would inevitably come into conflict with the intent and spirit and letter of that act m many of its administrative impacts.

Representative Griswold. Under this act, as you read it and as I read it, under the provisions of this legislation, coal produced under fair labor standards in Indiana and sold in Kentucky would not have to compete with coal produced in Kentucky under sublabor conditions, even though the coal produced in Kentucky was sold entirely within the confines of the State of Kentucky; is that not correct?

Mr. Lewis. I am not just clear as to how that would affect the coal industry there.

Representative Griswold. Understand, I am taking into consideration the fact that you have now the Guffey Coal Act, but under the provisions of this act.

Mr. Lewis. I frankly think that section 5, if enacted by Congress, would also be in conflict with the provisions of the Guffey coal stabilization bill, and I am all for striking out section 5 and simplifying this act.

Representative Connery. Will the Congressman yield?

Representative Griswold. Yes.

Representative Connery. As I understand your question, if the coal mined in Kentucky under sublabor conditions, substandard labor conditions, came in competition with the coal mined in Indiana under fair labor conditions, the competition phase of the matter, in view of the decision of the Supreme Court in the Wagner-Connery Act in the Jones and Laughlin case, would make the Kentucky concerns come up on their wages or they could not ship in interstate commerce.

Representative Griswold. The purpose of my question was just, as a matter of fact, Mr. Connery. We will presume that the coal is produced in Indiana under fair labor conditions. Coal produced in Kentucky is not. But the coal produced in Kentucky under substandard labor conditions is sold entirely within the State of Kentucky.

Representative Connery. It could not even be sold in Kentucky.

Representative Griswold. Under this act, as I understand it, that coal produced in Kentucky could not even be sold in Kentucky in competition with Indiana coal.

Representative Connery. Until they came up to the wages set by the Board.

Representative Griswold. I do not know whether I am correct on that or not, but that is my understanding of the bill.

Representative Connery. That is right.

Representative Griswold. Mr. Lewis, you are familiar, I know, much more than I am with the set-up of the Board under the Guffey Act. It is composed of seven members, I believe?

Mr. Lewis. Yes.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 284]

Representative Griswold. The Board under this act is composed of five members which shall be selected as nearly as possible with the geographical situation in mind, but there is not anything mandatory. Are the provisions of the Guffey Coal Act for the appointment of the Board practically the same as this other than that so many representatives shall represent labor, and so many representatives industry, and so many the public?

Mr. Lewis. There is no geographical restriction on the selection of the Board, and under the Guffey-Vinson Coal Stabilization Act there is the provision that no two commissioners shall come from the same State. It was to be composed of two operators, two miners, and three representing the public, and in order to give geographical representation to provide one operator from the North and one from the South and one mine worker from the South and one from the North, although that was not necessary as far as the mine workers were concerned. That is the reason the number is seven instead of five.

Representative Griswold. But, as a matter of fact, in the appointment of that board, the weight of the appointees went a little on the side of the operators, did it not?

Mr. Lewis. I would rather not comment on that at this time.

Representative Griswold. I see that the appointment of this Board, Mr. Lewis, is important, and, as I understand it, I was reading the lives of the appointees the other day in some magazines—maybe yours—where two of these operators are in reality operators at the present time, and one of them who was appointed as the representative of the public had been formerly connected with the operators; is that true?

Mr. Lewis. I don’t know that that is correct in any substantial sense.

Representative Griswold. I was just wondering if a man who had formerly been connected with the operators would not have his bias and prejudice and experience more with the operators than with the general public?

Mr. Lewis. Generally speaking, I think the Board is representative in having three of the public and two of the operators, one from the North and one from the South, and two men who have had practical experience as miners.

Representative Griswold. Don’t you think in the set-up of this Board which consists of only five members, and they are going to handle all industries and not just one such as the coal business but all industries in the United States and all labor practically will be affected by their decisions, don’t you think that it would be well to lay down mandatory regions or something from which these members of the Board shall come?

Mr. Lewis. I had not given any consideration to that. Of course, I appear here as an exponent of the proposition of lessening the amount of what the Board will have to do. Under section 5,1 think a board of three or five or seven or nine or eleven will have too much work to do, and that it can be simplified if section 5 is stricken out. And the duties of this Board are limited to the application and administration merely of a minimum wage act of 40 cents an hour and so many hours a week.

Representative Griswold. And that their powers not go beyond in any way the actual fixing of the minimum wages and the maximum hours. That is your position?

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 285]

Mr. Lewis. That is right.

Representative Griswold. That is all I have, Mr. Chairman.

Representative Connery. Mr. Welch, of California.

Representative Welch. Mr. Lewis, one of the purposes of this bill is to spread employment. Can you tell the committee how many men are unemployed in this country at the present time, or approximately how many?

Mr. Lewis. I cannot add to the committee’s knowledge on that question, aside from public information which everybody knows—the reports of the various agencies and the estimates that are made by the Works Progress and other governmental instrumentalities to Congress.

Representative Welch. I have not heard the last estimate. Have you?

Mr. Lewis. I could not recall it at the present moment.

Representative Welch. In your judgment, how many men are unemployed in the country at the present time?

Mr. Lewis. My judgment would be rather unimportant on that, because I have no actual knowledge, Congressman. I could only summarize the reports of these various agencies, the report of the American Federation of Labor, and the various governmental agencies and their reports to Congress, the reports of the various agencies of the manufacturers and employers. In other words, I don’t know how many men are unemployed and I don’t know anybody who does.

Representative Welch. Thank you.

Representative Connery. Mr. Lambertson, of Kansas.

Representative Lambertson. Mr. Lewis, would you rather see this bill reported adversely than see it reported with these sections 5 and 23?

Mr. Lewis. I did not quite get that question.

Representative Lambertson. Would you rather see this bill reported adversely than reported with sections 5 and 23 in?

Mr. Lewis. Well, I would not want to put it that way, Congressman. I think that the bill is entirely meritorious, eminently economically sound, and justifiable from every standpoint if we do not undertake in this measure to set up a board with power to fix the wage structure of industry.

Representative Lambertson. And do you fear that section 5 and the power given the Board therein, they might assume to make it similar to the Kansas Industrial Act of 1920 or something like that?

Mr. Lewis. Congressman, I am not sure what would follow the finding and publishing and fixation of a minimum fair wage in, say, the lumber industry by this Board. They would make an investigation and they would appoint an advisory commission, they would consider all of the factors set forth in section 5 and finally emerge with a recommendation for so much an hour and so much a month as being a fair minimum wage. If the men in that industry had an opposite view and felt that the wage found by the Board was inadequate and one with which they were in opposition, and resist that finding, I am not sure under this act what would be the action of some of our courts on that question. The employers would publicize the country and say that this is a fair wage that we are offering these men, who are arbitrary in their nonacceptance, the wage was found by a Government agency after fair analysis and proper examination, and would perhaps say, “We propose to go into a court of equity to

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 286]

restrain all and sundry from opposing that finding”, and I am not sure what some of our Federal judges would do under those circumstances, knowing some of the Federal judges. Then we would have the impossible situation of men being ordered by the Federal judiciary to remain at work under a finding that they regarded as unjust.

Representative Lambertson. In other words, you would rather see the labor have the power that it has today to strike and take care of itself whenever necessary, rather than under any Federal board which even might be appointed under the present President?

Mr. Lewis. I think it is perfectly meritorious and justifiable for the Government to step in to protect and lend its influence to improve the economic status of that submerged element in our working people who are incapable of helping themselves and whom the organized labor movement has not been permitted to serve, and to whom collective bargaining is unknown now or in the near future, and establish a basic minimum wage. I think that is entirely proper economically and legally sound, but I do not think that under section 5 of this act the Congress can afford to set up an instrumentality here and vest it with all of the broad powers that may be necessary to confirm wage fixing as such in the country, and then go through a struggle of some years with our Federal judiciary to determine whether, alter all American workmen are free men or indentured servants.

Representative Lambertson. If this bill is to be reduced to merely a minimum proposition, it is not hardly necessary to have a separate board to administer it, is it?

Mr. Lewis. Well, that is as the Congress may decide. I suppose that any kind of a minimum has to be at least policed by some agency. There has to be some central authority with whom complaints should be filed, and procedure with regard to enforcement will have to be worked out.

Representative Lambertson. That is all.

Representative Connery. Mr. Smith of Maine.

Representative Smith. Mr. Lewis, for the same kind of industry, do you believe in a minimum wage for all sections of the country?

Mr. Lewis. Yes; I believe in this minimum for all sections of the country and all industries. I think this minimum is so low that any industry that qualifies as an operating entity could pay this wage.

Representative Smith. What effect in your judgment will the raising of wages and the lowering of working hours have upon the small businessman?

Mr. Lewis. I think it will have a beneficial effect. I think the small businessman is dependent upon the income of his community for his profits and for the successful conduct of his business. Anything which will tend to increase the annual wrage income of the workers in his community will be a boon to the small businessman.

Representative Smith. I am glad to hear you say that, yet I am wondering a bit how with less capital, and perhaps less efficiency, how the small man can compete with the larger?

Mr. Lewis. Of course, the relationship of the small merchant to the large one is a matter entirely beyond the purview of our present discussion here, but I think that anything that will increase community income where the small merchant is operating, will operate to his advantage. Of course, he will still have the problem of his relationship with larger units in his own industry or field of service.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 287]

Representative Smith. In your opinion, will it be necessary, if this bill is passed, to rearrange reciprocal tariff relations?

Mr. Lewis. I do not see how it could be done until this bill is passed, and until a record of performance is obtained that will show its effect upon commodity shipments, imports and exports. I do not see how any approach could be made to the question until a record has been made.

As a matter of fact, I think, under the proposals which I suggest, the impact on the possible tariff change in the structure will be rather insignificant.

Representative Smith. There should be, in your opinion, no allowances made for the factory that is equipped with inefficient machinery, and that the minimum wage should apply just as well.

Mr. Lewis. Do you mean to reward inefficiency in business by giving the inefficient employer the right to hire human beings at a lesser wage?

Representative Smith. I don’t think so, but that has been suggested and that is why I am asking.

Mr. Lewis. I think that is unsound from about every approach.

Representative Connery. Mr. Lewis, right along the line, so that they will not have to come back to it when I reach my own questions—if Mr. Thomas will yield—in the first 6 months of this year, there were about 400,000 tons of Welsh coal came in here from Wales and from Russia and can be delivered in the port of Boston for $3 a ton less than your anthracite coal from Pennsylvania can be delivered in the port of Boston after all of the landed costs have been paid on the foreign coal. If this bill comes into effect, suppose they went to a 30-hour week in the mines—I don’t know what your ordinary wage is— but certainly your wages in Russia and Wales are far below what they are here, and we opened the market that way to the foreign coal. Don’t you think you are going to suffer here unless something would be put in, either permissive or otherwise, to allow this board to or allow the Tariff Commission, after advising with the President, to take care of that situation of foreign imports?

Mr. Lewis. Are you speaking of the Welsh importations or the Russian?

Representative Connery. Both. About 400,000 tons since January.

Mr. Lewis. Three hundred and eighty-eight thousand tons of that was Russian coal which paid $2 a ton import tax. The Welsh coal comes in duty-free under the favored-nation arrangement. The imports from Wales are insignificant. The total production of anthracite in Wales is only 3½ million tons per year as contrasted with our present 50,000,000 tons. Obviously, England could not export her entire production of anthracite, and the amount that will be exported from Wales I think is not in itself substantially important.

Now, the question of the Russian importations—that ran up from about 250,000 tons in 1935 to 388,000 tons in 1936. That coal paid the import duty of 10 cents a hundred pounds, or $2 a ton. As a matter of fact, that is the only country against which the coal tariff runs, Russia. That $2 a ton does not stop the importation of Russian coal. $5 a ton would not stop the importation of Russian coal if Russia wanted to export that tonnage to build up its trade balance in America. Russian coal has no cost of production that can be

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 288]

translated or compared with our costs. One cannot find a cost of production in Russia and measure it against any tangible equations.

The answer to the question of Russian coal is not through the application, in mv judgment, of a greater coal tariff. It is a question of the State Department perhaps working out an arrangement of that question voluntarily with the Soviet Republic.

Representative Connery. Well, under the N. R. A. we had the proposition that the President, if he saw fit, if any imports interfered with the administration of the N. R. A., to put an embargo on it, or he could place a tax on the difference between the cost of production in this country and abroad. Would you favor that going into this bill, giving the President that power?

Mr. Lewis. I think something like that certainly is all right. I feel, perhaps, that this whole subject of the Russian importation may possibly be worked out by Government agencies, but in the event it cannot be worked out I surely would favor the right of the President to put an embargo on imports, if and' when it became necessary.

Representative Connery. I have one more thing. Mr. Thomas is next and I do not want to take his time. There were 500,000 pounds of canned beef brought in by the Chicago packers, and I forget how many head of steers that would amount to in Texas, but it is quite an amount. Now, the same thing applies to cattle as it does to your coal and that is why I ask these questions in reference to foreign imports. If something does not go into the bill to give the President at least the power to embargo it, to tax it, we might find ourselves in the situation, and do you believe we would find ourselves in the situation of where we would be opening our ports to cheap labor and long hours, driving our manufacturers and our cattlemen out of business?

Mr. Lewis. I do not know that some of our ports are not now open on that basis. I do not know that anything in this bill would materially complicate that problem. I think that the whole question of the tariff structure is a separate question which has to be considered by Congress and the administration, and I do not think that it can be well considered in connection with this bill.

I might point out, for instance, that the Bethlehem Steel Corporation annually imports 15,000,000 tons of iron ore free into this country. The Bethlehem Steel Corporation, which is the low-wage corporation of the steel industry, is behind the Republic Steel, the Youngstown Sheet and Tube, in resisting collective bargaining in that industry. The Bethlehem Steel is trying to protect this low-wage structure in its mill, and trying to protect the special privileges and special cost advantages that it has over its competitors in the industry by maintaining its right to have the 15,000,000 tons of iron ore enter duty-free. So if you are merely interested in the question of tariff equities as such there is an ample field for all of our minds to operate, independent of any consideration of this bill.

Representative Connery. You would not object to something going into the bill that would give the President the same power that he had under the N. R. A.?

Mr. Lewis. I would have no objection at all, Congressman. I merely suggest that this bill, as I see it, which creates a minimum wage of 40 cents an hour in all industry affected by the bill, would not of

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 289]

itself create a complicated tariff problem. The tariff problem, if it is complicated, and I rather think it is, is with us anyhow and perhaps is entitled to definite, separate consideration.

Representative Connery. Mr. Thomas.

Representative Thomas. Mr. Lewis, my question is somewhat similar to that of Congressman Smith, namely, do you see any danger in this bill of the concentration of business in strong hands?

Mr. Lewis. You mean this bill as such?

Representative Thomas. Yes, sir; as it is now drawn.

Mr. Lewis. It had not occurred to me that there was such a potentiality.

Representative Thomas. Let me ask you a hypothetical question and see what you think about it. Suppose we have here a business that is barely able to keep its head above water through one or more causes—maybe you have a poor management, maybe you have an insufficient capital structure, and for those reasons the business is just barely able to get along; consequently it has a long workweek, and it pays low wages; suppose this act goes into effect, and the effect of this act upon that particular business will be this—that that business will have to decrease its working hours 20 percent per week and increase its pay, say, 15 or 20 percent a week; do you think that the act then would put that business out of operation, or what effect would it have upon that business?

Mr. Lewis. Well, I would not know without a more particular knowledge of the business than you have indicated in your question. I think, by and large, that business would tend to increase its volume and probably increase its profits in that manner. However, the records are that nearly two-thirds of all the corporations and business enterprises fail and one-third survive. There is a constant change there. I could not undertake to say, with any degree of sound judgment, what would happen to a hypothetical business such as you describe there.

Representative Thomas. That question leads me to this one, Mr. Lewis. It is apparent to me that unless there was some elasticity in the act, which is not there now, if this act goes into effect, simultaneously the business that I have described would have to fold up.

Senator La Follette. Will the Congressman yield there?

Representative Thomas. Just a minute, Senator. Let me finish this, and I will be glad to yield. I am just wondering if you think it is at all possible and practicable to have a differential within the same industry.

Mr. Lewis. I do not think it is practical at all to have a differential on such a low minimum. I cannot conceive of what kind of business it might be that would fail under the reasonable increase of cost that this bill might apply. For instance, a man with two employees might have his wages increased $2 a week, a total cost of $4; the reduction in hours might cost him another $4, or $3. Well, if he is so near failure that $7 or $8 a week increase will ruin his business, I do not think he will be safe anyhow. If he is that close to the sheriff, I think the sheriff will get him.

Representative Thomas. The sheriff will get him sooner or later, regardless of this act

Mr. Lewis. Yes.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 290]

Senator La Follette. I just want to call attention to this provision on page 12 with regard to the oppressive wage, which reads:

Having regard to the policy of the Congress to extend the applicability of the provisions of this Act with respect to an oppressive wage to all employments within the scope of this Act as rapidly as possible, the Board shall from time to time by regulation or order declare such provisions applicable to employments within the scope of this Act as rapidly as the Board finds that such provision can be made applicable to such employments without unreasonably curtailing opportunities for employment.

Does that not give the Board discretion as to the rapidity with which it puts these orders or regulations into operation, taking into account the possibility of closing up establishments and thereby- curtailing the opportunity for employment? In other words, is not the discretion there in the act?

Mr. Lewis. How does that impact on you, Congressman?

Representative Thomas. If that paragraph, Senator, will be construed to apply to whether or not the minimum wage itself shall go into effect, then I think that will save the situation that I pointed out ; but if the minimum wage goes into effect, ipso facto, and this particular sentence that you point out here is construed as giving the Board power to later come along and raise that standard set by the act itself, then I have some grave doubts as to the wisdom of it.

Representative Connery. Had you concluded, Mr. Thomas?

Representative Thomas. Yes.

Representative Connery. Senator Murray, of Montana.

Senator Murray. I have nothing.

Representative Connery. Mr. Iglesias? Do you want to question the witness?

Representative Iglesias. No.

Representative Connery. Mr. Wood, of Missouri.

Representative Wood. Mr. Lewis, there seems to be a great apprehension in the minds of a great many people that if this law is enacted and a 40-cent minimum is established, if wages were elevated and hours were reduced, that that will cause an undue rise in the cost of living. Now, the Ohio coal fields instituted a coal loader some years ago. As I understand, the coal-loading machine operated by 2 men took the place of some 30 or 40 coal miners who previously had produced coal without the application of the machine. Now, by the institution of that coal-loading machine, which caused the operators to raise their dividends, did that appreciably affect the wages of the coal miners? Did the coal miners’ wages suddenly go up?

Mr. Lewis. No; the wages did not go up, Congressman, because of that factor. As a matter of fact, mechanization in the mining industry proceeded at a faster rate in 1936 than the years previous, and the displacement of manpower that has taken place in the coal industry by the introduction of those modern appliances will be greater this year than in 1936, so much so that upon the demand of the mine workers the industry has appointed a joint commission to make a scientific study of all the factors involved in the increased use of machinery in the mining industry. As a matter of fact, one of the very great questions that affect our country at the present time is whether or not the workers are going to be permitted a participation in the increased efficiency of productive industry.

Right now our increased volume of business, our so-called prosperity, carries with it the seeds of much greater unemployment in this country,

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 291]

because as plants increase their volume and increase their sales realizations and their margins of profit they have more money and more credit to modernize plant facilities, buy new- machinery, utilize energy, and displace human hands. That is one of the great questions that affect our country now and it is one of the things for which no appreciable solution has been found either by Congress or by industry, or by labor.

Representative Wood. In other words, when the coal-loading machine was established the mine workers received no consideration with reference to a raise in wages and a reduction in hours, except by and through collective bargaining?

Mr. Lewis. That is right, Congressman. I might say right at this point that there has recently been demonstrated a coal-loading machine that loaded in one 7-hour shift more than 1,100 tons. That is the work of 110 men. It takes 11 men to operate the machine as a unit. That machine will stay, of course, and others will follow. Eleven men remain and 99 men go. Where do they go? That is the question that confronts the coal miner—where do they go? There is no answer to that.

Representative Wood. It seems to me like the greatest danger is that the workers are not permitted to share in the benefits that follow from science and invention in the application of labor-displacing machines, that the employer reaps the benefits.

Mr. Lewis. That is one thing that is uppermost now in the minds of all these millions of workers who are joining the unions of their industries. They are doing so with the hope and the determination on their part to insist upon a participation in the increased efficiencies of modem productive industry, that they have been denied in the past.

Representative Wood. Now, following the World War and during the World War the basic day for the mine worker was 8 hours, was it not?

Mr. Lewis. That is right.

Representative Wood. The average?

Mr. Lewis. Yes; 48 hours a week.

Representative Wood. That is right, Now, the mine workers have 35 hours a week. Can you notice any difference in the price of coal to the ultimate consumer in 1921 and 1920, during and following the World War and today, although the mine workers are working 13 hours a week less and probably drawing a higher wage than they did in 1921?

Mr. Lewis. It is substantially the same, Congressman. I might say that in the mining industry the shortening of a work day has always been accompanied by an increase in the per man per day production and a cheapening of the cost of production. From the 12-hour day down to the 11, down to 10, down to 9, down to 8, and down to 7, the per man per day productivity has always increased, and with respect to that reduction from the 8-hour to the 7-hour day in the industry a year or so ago, in 1935, the operators are unable to present any comprehensive figures to show increased cost of production, while, as a matter of fact, we have information which shows that in certain districts the operators made a profit and actually lowered their cost of production by reducing from the 8-hour day to the 7-hour day. One particular field that comes to my mind at present made a saving of 2½ cents a ton in the cost of coal by changing from the 8-hour day to the 7-hour day.

=================================================================================================================================

[PAGE 292]

Now? of course, there are many factors that enter into that question. The miners in our bituminous and anthracite industry are the most productive of any miners in the world. The British miner produces on an average of 1 ton per man per day; our mine workers produce 5 tons per day per man employed, on the average. Many factors enter into it. We have a faster tempo of operations, greater productivity of the American miner, utilization of energy and machines, fine engineering, and good management.

That merely indicates what industry will do. Industry can give a participation in greater leisure and shorter hours to the American workman, giving him a wage that will maintain his consumer buying power, but industry has not been doing it.

Now, that same argument is an argument that shows that the shortening of the hours is not, up to this point, a complete answer for the unemployment question, because as efficiencies increase displacement of manpower continues. The answer to that is nothing but a progressive shortening of the hours.

Representative Wood. Now, we agree that the passage of the Guffey coal bill did put out of business thousands of small so-called employers. It has been the experience in my State, and I suppose that was the experience everywhere, that we had thousands of small employers, so-called employers, that ran a cooperative mine, what they call wagon mines, and they produced coal, and the operator himself was practically an employee, and if he made from 75 cents to a dollar a day it was a tremendous profit for his effort, and he constituted the cutthroat competitor of the coal industry. Do you know of any reason why that sort of business should survive, a business that cannot pay wages, that cannot work its employees reasonable hours, that cannot maintain a sufficient dividend and profit to build up his capital structure so he will be in somewise substantial; that is, he will be able, in somewise, to guarantee reasonable steady employment to his few employees? Can you see any reason why the employer that I have mentioned, or in any industry, should have any good reason to exist?